In the twelfth century across medieval Europe emerged a feminist movement called the Beguines. These women cultural agents, defying societal norms, and “freeing themselves from ecclesiastical control” (Satta, 2020), carved a space for themselves as self-independent caregivers, textile workers, business owners, artists, educators, and spiritual seekers in a time when women could only be nuns or wives. The Beguines “pooled their resources in order to serve the sick and destitute by building and operating infirmaries and almshouses” (Swann, 2014). However, the freedom that it was enjoyed in the twelfth century would not last long as in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Inquisition under the popes of Rome persecuted those who were Free Spirits (free thinkers and artistic creators) and did not obey the rules of the Church and the State. The very existence of the Beguines, challenging traditional boundaries and building cultural influence, threatened the established order, ultimately leading to their silencing, and final extermination as in the case of mystical writer Marguerite Porete.

The Beguines practiced a form of motherhood that extended beyond blood ties. They were caregivers, midwives, and healers to the entire community. This paper focuses on two contributions made by the Beguines in the field of education and healthcare. I argue that the Beguines, often celebrated for their contributions to their communities, embodied a concept of motherhood that transcended biology. Motherhood, in this context, can be understood as a broader concept of nurturing and caregiving, extending beyond a woman’s biological role.

The Beguines’ radical departure from traditional gender roles and their subsequent persecution underscore the power dynamics of the time. It is crucial to remember the Beguines, who were silenced but still served as women agents of history. Their erased narratives offer a powerful counterpoint to patriarchal narratives, which often overlook women’s capacity for cultural influence, control over their own bodies (beyond Western thinking male political agendas), and their collective care as healers and mothers.1

Facing persecution and accusations of heresy by Pope Clement V in 1311, Beguine communities started to decay. By reclaiming the Beguine legacy, we can challenge the historical invisibility and criminal persecution they endured from the Inquisition and the State, paving the way for a future where women and girls have a voice and agency without fear of persecution. The Beguine environment of medieval Europe, where religious and political cultural constructs were tightly linked against women’s freedoms, made it challenging for women to write their history. Gayatri Spivak’s term subaltern aptly describes these hidden, marginalized women who were forced into silence (2002). As an example to avoid being mistaken for prostitutes, Beguines often wore loose-fitting gray tunics and head coverings, similar to nuns’ habits, earning them the nickname “Gray Sisters” (Swan, 2014). This action enforced uniformity further obscured their identity and agency.

However, beyond their survival, the Beguines emerged as potent women cultural agents, actively participating in and shaping the cultural fabric of their communities. They challenged existing norms, created new narratives, and left an indelible mark on their communities, the Beguinages. Operating outside the confines of convents in the city, their homes and communities became centers of learning, offering literacy and religious instruction in vernacular language to women and children often excluded from formal education because Latin was the language of the privileged. Through their writings, music, art, and oral traditions, these women preserved and disseminated healing knowledge and spiritual wisdom.

I describe two important factors that made the Beguines unique and important cultural agents: their roles as educators and healers. Firstly, as writers and artists, the Beguines taught lay women and their communities. Figures like religious writer Porete exemplified this by feminizing language and transforming it into an erotic language of impregnation. Secondly, the Beguines embodied a profound connection between womanhood and motherhood. They took responsibility for the care of all children, not just their own, and developed childbirth techniques infused with religiosity, as exemplified by the use of the psalters of Margaret of Antioch.

Firstly, the power of language of Porete, an independent itinerant woman writer, authored The Mirror of the Simple and Annihilated Souls and Those Who only Remain in Will and Desire, a challenging exploration of love and divine union expressed through feminine imagery and feminized old French. Such genederized writings empowered lay women, but religious women were not allowed to teach theology openly. Henry of Ghent declared before 1290, that no woman could be a Doctor of Theology. However, a woman could teach other women and girls privately, in silence, hidden from the public life (McGinn, 1994).

I find in Porete’s text a continuous pouring of feminine subjectivity in the form of language. For instance, Porete’s notion of annihilation suggests a total self-sacrifice in the mystical union to and for “Lady Love,” one of her many interlocutors in The Mirror. Her manuscript addresses readers as “Ladies,” “Lady Reason,” and “Lady Nature” (Wright, 2009). Notably, while “l’amour” (love) is masculine in French, Porete bestows feminine agency upon it. Love is constantly addressed with feminine pronouns and other terms of endearment, such as “maitresses,” as noted by scholar Maria Lichtman (1994). Similarly, the Soul becomes “our dear madame,” as expressed in the French phrase, “notre chère dame, dites nous un peu qui vous êtes, pour nous parler ainsi” (Michel, 1984, p. 137).

McGinn notes that Porete ‘simple soul’ had a teaching mission that confronted the hierarchy of the church and the use of a genderized vernacular language facilitated her mission (1994). Linguist Noam Chomsky frames that language is not only a form of communication, but shows underlying beliefs, “reflects power interests” (2011) and reinforces existing structures of power. As a prominent woman cultural agent, Porete challenged these structures through her subversive use of language. Likewise, Luce Irigaray (1985) in This Sex calls to subvert the “phallocratic” power structures embedded in all discourse, including philosophical and political, and to seek liberation through new forms of expression as Porete does with feminine old French and resistance to the Virtues and other impositions. Porete suggests continuing to evolve beyond Reason and Knowledge via Love toward God. The Virtues, Sacraments, and other Church rules are not to be followed. Maria Lichtman states that in “her feminine reordering of love over reason as well as the great church of god’s true lovers over the lesser church, Porete subverted patriarchal structures” (1994). The lesser church is the institution of the church, donkeys, and beasts according to Porete while the real Church is the great one, the one that holds Love. Porete was forbidden to teach her manuscript and was burned in 1310 in the place of Gèvre, Paris; despite initial endorsement by theologians, accusations of heresy led to her arrest and final execution.2 Porete’s fate served as a chilling reminder of the limitations imposed on women’s cultural agency in a male-dominated society.

In the Song of the Soul, Porete transforms Fine Love into Loyal Love in the last stage of Porete’s spiritual journey, where the Soul is finally separated from everyone, from everything, including the Virtues, continuous repetition in Porete’s teaching methodology. From a beast serving the Virtues, the Soul becomes free of will, and at that moment, Loyal Love enters the Soul, explained in sexual language as shown in the following fragment of the Song of The Soul:

I have said that I will love him

I lie, for I am not

it is he alone who loves me

he is and I am not

and nothing more is necessary to me

than what he wills

and that he is worthy

he is fullness

and by this am I impregnated

this is the divine seed and Loyal Love (Mirror, p. 201)

Nothing more is necessary to the Soul and her beloved, Loyal Love. Through sexual language, the Soul says that God is complete and that her beloved’s divine seed has impregnated her. Love is why the Soul is willing to give up will and desire. In the Poretian threefold, no wanting, not having and not knowing, God that is nothing but the Light, the Source… impregnates and the Soul come back to her origin, unique to Porete’s theology (Marín, 2010).

Secondly, the Beguines were pioneering women cultural agents who offered unique teachings to women about femininity, self-respect, and they protected motherhood, the self of the mother and the welcoming of new life. Beguines were midwives and caring mothers providing a wide range of social services, not only caring for the dead, but assisting in childbirth, and offering refuge to abandoned children. Beguine communities built schools, educating both boys and girls. The Beguines believed education strengthened society and their own work. Womanhood and motherhood were tightly interconnected as the Beguines were caring mothers and did not discriminate but welcomed babies and children in their own homes and facilities (Swann, 2014).

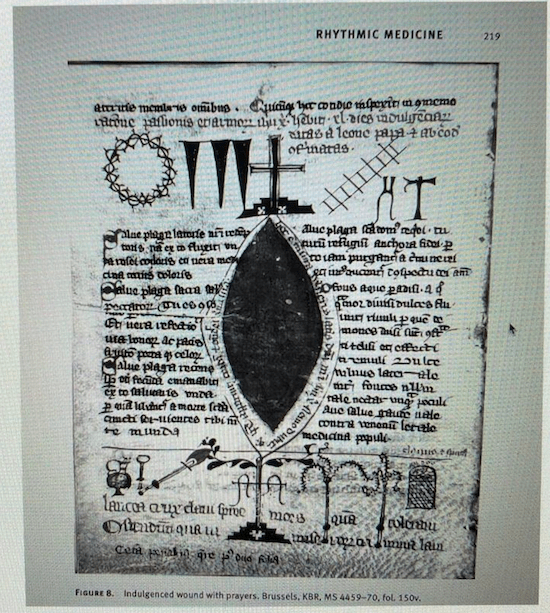

In women’s religious communities of the thirteenth century Southern Low Countries, the psalter, a book containing psalms for religious devotion, took on an unexpected role. The Beguines already used the psalter for prayer and penance, but they discovered its potential as a healthcare tool. The psalters themselves became a kind of technology for women to learn about and practice healthcare.

Psalter books circulated within women’s religious communities in the southern Low Countries, used and modified by the Beguines for healthcare knowledge and practice. This fact revealed women cultural agents’ distinctive approach to care, one characterized by affective performance and prayer. Some were similar to scholastic physicians of their times. Religious charms were meant to take care of health, for example, “wound meditation from women’s religious communities in the region was associated with explicit forms of healthcare, such as relief from the pain of childbirth” (Ritchey, 2021).

Images like midwives attending the Virgin Mary’s birth provided visual instructions. Stories like that of Saint Margaret, Margaret of Antioch, known for easing childbirth, were included in some psalters (Figure 1). These stories could be recited or even the image placed on the laboring woman’s abdomen. These elements in the psalter served multiple purposes. They instructed women on how to care for mothers in childbirth, helped them remember important stories and practices, and linked their daily work of caring for others to their religious devotion through prayer.

Figure 1

The Life of Margaret appears in a pictographic cycle in the bottom margin under psalms, a visual hagiography that women cultural agents, specifically Beguines could have used to care for parturient women. Childbirth assistants could use Margaret’s images, the recitation of her Life, and even the codex copy of the Life itself to ease labor. In the psalms Margaret herself is illustrated to be escorted to her execution (Figure 2). Margaret was sanctified and became the patron of childbirth and pregnant women (Ritchey, 2021). In her last instants, before being beheaded, a response from a celestial voice proclaimed that her invocations were given as Margaret requested God that any pregnant woman might call on her for a safe delivery.

Figure 2

Despite the persecution of women who were educators and healers, the Beguines’ legacy endured for centuries, although today these women do not exist, the Beguinages, their buildings and courtyards persisted. It is believed that the last Beguine died in 2013, Marcella Pattijin who lived in Sint Amandsberg, Belgium (Satta, 2020). Beguine’s contributions to healthcare, education, and spiritual exploration continued to resonate nowadays as their story serves as a powerful reminder of the silenced voices of women throughout history and the ongoing struggle for women’s rights. Western patriarchal systems exterminated women’s independent thinking and agency.

In conclusion, the Beguines, as visionary women cultural agents, embody the complexities of female agency in history. They carved a space for themselves, contributing significantly to their societies and communities by healing and educating, only to be silenced by a system that felt threatened by their independence, intelligence, and unorthodoxy. The Beguines story not only sheds light on a fascinating chapter in European history but also compels us to recognize and celebrate the contributions of women who dared to challenge the status quo, even in the face of repression. Ultimately, The Mirror of Porete and The Life of Margaret stand far from being merely religious teachings or historical facts. Instead, these are lessons guided by a new feminine language led by Love that represents womanhood, motherhood, feminine liberation, freedom over the patriarchy of Reason and Knowledge in Western thought, a testament to the transformative power of feminine language, and spiritual healing, that questions themes of patriarchal, and hierarchical categorization such as gender, the feminine experience, and divine Love. Porete’s use of genderized language is more than a radical act of resistance; it is a defiance of what is allowed for a woman to do, say, possess, learn, share, have, think, and believe. Porete’s Love and Annihilation protects the oppressed, experiences the mystical in the physical world, and teaches the underserved in Latin-ruled educational settings; while Margaret’s psalters heal and comfort the expectant mother in the childbirth via prayers and spiritual rituals.

As a movement, a feminist one, the Beguines endured for centuries despite crusades, plagues, famine, and church censure. Through centuries, these women lived together in communities, dedicating themselves to serving others. What is the message we receive today in the twenty-first century by the Beguines? The Beguines were not a religious movement as they did not even take vows, but the Beguines were intelligent and independent women playing the game of the patriarchy to survive; they were business and landowners, builders, midwives, educators, healers, in short, women cultural agents.

Works Cited

Babinsky, Ellen L. (1993). The Mirror of Simple Souls. Paulist Press. 1993.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. (2002). ‘Who Claims Alterity’, p.1092-1096. Art in Theory 1900 – 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas 2nd Edition by Charles Harrison (Editor), Paul J. Wood (Editor) 2002.

Harrington, Joel F. (2018). Dangerous Mystic: Meister Eckhart’s Path to the God Within. New York: Penguin Press, 2018.

Irigaray, Luce. (2021). A New Culture of Energy. Beyond East and West. E-book ed., Columbia University Press, New York. 2021.

Irigaray, Luce. (1985). This Sex that is Not One. Cornell University. 1985.

Live of Saint Margaret of Antioch. British Library’s Egerton 877 https://stmargaretmarina.omeka.net/life-of-saint-margaret-or-marina-of-antioch

Marín, Juan. (2010). Annihilation and Deification in Beguine Theology and Marguerite Porete’s Mirror of Simple Souls. Harvard Theological Review, Jan. 2010, Vol. 103, No 1 (Jan. 2010), pp. 89-109.

McGinn Bernard. (1994). Meister Eckhart and the Beguine Mystics. Maria Lichtmann. The Mirror of Simple Souls Mirrored. The Continuum Publishing Company. 1994.

McGinn Bernard. (1994). Meister Eckhart and the Beguine Mystics. Michael Sells. “Unsaying” and Essentialism. The Continuum Publishing Company. 1994.

Michel, Albin. (1984). Le Miroir des Âmes Simples et Anéanties. E-book ed., Spiritualités Vivante. 1984.

Miller, Tanya Stabler. (2014). The Beguines of Medieval Paris: Gender, Patronage, and Spiritual Authority. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Orelus, Pierre. (2011). W. Rethinking Race, Class, Language, and Gender. A Dialogue with Noam Chomsky and Other Leading Scholars. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 2011.

Patricia A. Geary. (2020). GNSH The Beguines of Medieval Europe: Mystics and Visionarieshttps://www.greynun.org/2020/02/the-beguines-of-medieval-europe-mystics-and-visionaries/ 2020.

Richey, Sara. (2021). Rhythmic Medicine: The Psalter as a Therapeutic Technology in Beguine Communities. Published by Ritchey, Sara. Acts of Care: Recovering Women in Late Medieval Health. Cornell University Press, 2021.Project MUSE. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.83168.

Satta, Gloria. (2020). www.osservatoreromano.va/en/news/2020-09/the-last-beguine.html 2020.

Stirler, Gael (2008). The Beguines women movement of the 13th century. Retrieved from http://stores.renstore.com/-strse-template/0808A/Page.bok

Swan, Laura. (2014). The Wisdom of the Beguines. The Forgotten Story of a Medieval Women’s Movement. Blue Bridge. 2014.

Wright, Patrick. (2009). Marguerite Porete’s Mirror of Simple Souls and the Subject of Annihilation. Vol. 35, Nos.3-4, September/December 2009. Mystics Quarterly. Manchester Metropolitan University. 2009.

Image Credits:

Figure 1 Reference: Indulgenced wound with prayers. Brussels, KBR, MS 4459–70, fol. 150v https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/255/oa_monograph/chapter/2834863/pdf

Figure 2 Reference:

http://ica.themorgan.org/manuscript/page/33/77075

Footnotes:

- The rise of merchants and a coin economy empowered women. The Crusades left fewer men and the Church was changing (Swan, 2014). This created a perfect storm for the Beguines. Europe’s booming cities, like Cologne with its 169 Beguinages (Harrington, 2018), provided fertile ground. With limited space, some Beguinages required dowries (Stirler, 2008). Even royalty, like King Louis IX of France, supported Beguines (Miller, 2014). By the thirteenth century, there were more than a million Beguines in Europe. ↩︎

- Lea, Henry Charles. (1992). A History of the Inquisition in the Middle Age. 2:575-578, 3vols. NY: Macmillan. 1922. Fredericq, Paul. (1896). Corpus documentorum inquisitionis haereticae pravitatis Neerlandicae, ed. 156-160. Ghent: J. Vuylsteke. 1896. http://www.uncg.edu/~rebarton/margporete. ↩︎