By Rachael Grad

Motherhood is mayhem. Working around my children and their messes−scribbles and scrawls amidst the dribbles and crawls−significantly changed my artmaking practice techniques. When I became a mother, I could no longer spend long days in the studio slowly layering acrylic oil paint brush marks on large surfaces. To make art, I had to carve out space and time for short bursts of creation. Carrying around a sketchbook and journal at all times enables me to find shorter moments to frequently draw and take notes. My daily drawings and journal writing allow me to generate art, while feeding into, and nourishing, my studio painting.

Although a mother’s role involves caring for her children, my drawings and writing are a form of active self-care for my artistic practice and well-being. In this paper, I explore how I witness, document, and engage in play as an artist. To seek inspiration and strategies, I research how artist mothers and caregivers find time to create. Artist diaries (Truitt), interviews of (ed. Carpenter Estrada) and essays by artist mothers (Huber and Kirtland), and the artist-mother open residency website (An Artist Residency in Motherhood, Clayton) serve as endless sources of ideas and motivation. My daily scribbles and scrawls, along with historical canonical artworks, provide a starting place for my own creative practice.

Finding moments within parenting chaos to make art is an ongoing challenge. I am limited by the hectic schedules of various children and adults living in the same home. My shared calendar with multiple family members is now like a Tetris game, slotting in the correct number of pieces in the form of activities and attention for each person. Nevertheless, despite my children’s messes, illnesses, and time demands, I can usually fit in at least one daily drawing. Between mundane “mommy” moments, i.e., feeding them and driving them to school/playdates/programs, I carve out minutes for an art practice. Drawing or writing, however, can be interrupted, often when my children draw on my work. Sometimes I abandon my drawings or notes when disrupted; other times I allow the work to become a collaborative project with my children. [Note 1]

I carefully hide sketchbooks, pencils, sharpeners, and erasers around my home and in my purse to be easily accessible. Typically, I sketch with pencil on paper, observing my children while they watch TV, read, or play. Often, I draw their toys and belongings before cleaning up. I make quick sketches of these domestic messes, clutter, and chaos. Before drawing, I ponder a series of questions: what is around me that I feel compelled to draw? Should I leave the toys as they are or rearrange them? Will this be a multi-day or month-long project? Or a specific idea that I explore one time only?

This art habit is easy to start and stop, and involves minimal preparation and cleanup. I can draw while waiting for my children at programs or appointments, as well as at home. Sketchbook drawing is a mobile practice. Sometimes I write notes about the drawing, my mood, or the environment. My writing and drawing/painting practices are usually separated. I have different sketchbooks or journals for each, and engage in them at different times of the day, and in varying ways.

My handwritten notes of the day are often barely legible, even to me. I am almost finished with my “One Line a Day” for 5 years journal [Note 2], in which I record daily activities, the weather, funny things my children said or did that day, projects in progress, or annoyances committed by family members. Several lines or sentences may mark each day, with some days more neatly recorded than others.

The writing (scribbles) and the drawings (scrawls) are my forms of note taking and documentation. My sketchbooks and written journals are very personal, and I rarely share the drawings or notes. Both the art sketchbooks and lined journals are diaries to me, so I am uncomfortable publicly exposing the drawings or writings in them. Unlike my art, these are private spaces for me to explore, experiment, and express feelings and moments of my family life.

My favourite drawing media are soft matte pencils, squishy Staedler erasers, and Holbein sketchbooks. [Note 3] However, I also draw and write on paper scraps, leftover packaging, and whatever is around. At different times, I have drawn the same stuffed animal daily for over six months, a realistic, manageable art project during difficult periods: during the first COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, for example, and after the birth of my children in 2015 and 2019. [Note 4]

My children are my unpaid life models, frequently squirming while I draw them as they watch TV or play. Most often they do not notice or mind that I observe and draw them and their belongings from life. They are constantly moving their stuffed animals and toys. So, I draw what I see and do not worry about finishing or about the resulting work.

Drawing daily allows me to have an art habit. It makes me feel better about the fact that I spend too much time hunched over screens and my car steering wheel. “Practice” seems too serious and formal a term for my scribbles, notes, messy scratches, and marks. I am reassured by Marcus Boon and Gabriel Levine’s (2018) wide encompassing description of art practice:

We can view the history of art over the last hundred years as a kind of seething, restless struggle with this reconfigured imperative to practice. The ethical mandate that art has taken on via its confrontation with existing material conditions has resulted in a splintering of art into more and more diverse objects, events and engagements–with the paradoxical result that basically anything that could be considered a practice might be considered art. (p.14)

My practice is a domestic, comforting habit of notation through marks; that is, I make notes and record ideas. I want to remember and record the shadows, lines, gestures, and feelings for that moment and future use. Drawing is my fallback when I want to make something, record a memory, or just feel more like myself. My drawings are often rough, messy, and inaccurate, with many scribbles and eraser marks.

My journaling in image and text is not a “Project” or a “Practice” (with Capital Ps) in the historic, enormous ways described by Boon and Levine (2018) throughout their article. My writing and drawing are small ongoing commitments and habits, like the “agreeable projects” described by Groys:

[I]n the eyes of any author of a project, the most agreeable projects are those, which, from their very inception, are conceived never to be completed, since these are the ones that are more likely to maintain the gap between the future and the present for an unspecified length of time. Such projects are never carried out, never generate an end result, never bring about a final project. (p.4)

Never finished, my daily drawings and sketches ferment and accumulate. They mutate from the paper in my mind and then come out warped and alien-like in paint gestures and brush marks. Reading over my daily writing journals, I realize that I concisely preserve what happened each day in one or two sentences. I enjoy reflecting on previous years and letting the lines, images, and words rest for the future.

The ideas settle and grow until I feel ready to incorporate them into my paintings or writing. Levine (2020) remarks that “[i]ntegrating home fermenting into daily routines alters one’s relation to ‘productive’ time” (p.202). Similarly, incorporating drawing routines changes my focus as well as how I work and produce art. Levine further argues that home fermentation is an intuitive way to scale and slow down (p.203). This leisurely process gives the body physical and spiritual regeneration to build strength, energy, and hope (p.203). Such transformations do not miraculously occur, because they require time, practice, and persistence, and the “work is often invisible: only a quiet bubbling reveals the complex degradations that are taking place beneath the surface” (p.261).

Slowly, with tiny marks and words, I build up a body of material. This process of notetaking through drawing and writing is small, because I sometimes spend only a few minutes a day on it. If needed, this practice can take up very little time or space. However, it can also be significant and expansive. My sketchbook drawing times vary between seconds and long hours. The accumulation of minute moments of mark-making, the intense observation of drawing from life, and describing daily events, add up. On the days I do not draw, I am moody, irritated and do not feel like myself. It is as if I did nothing for myself on those days, and a part of me is unsatisfied. The feeling is like forgetting to brush my teeth. Drawing is necessary self-care for me, and a way to slow down and get back to my early traditional artistic training and roots. Other artists use drawing and painting as self-care (Swift) and to lead their individual or group therapy (Malchiodi). Drawing takes different shapes in my life.

I set up repetitive projects and strict constraints involving daily drawing and painting. With my predetermined rules, I focus on the creation actions and do not worry about generating new ideas or strokes of brilliance. In the past, I spent too much time pondering how, what, and why to draw and paint. Now I like to have pre-decided-upon ongoing projects to which I can always revert and thus continue creating. I avoid overthinking the rules and restrictions, getting stuck on thoughts which block me from making work.

I create as research and research for creation. Scholars Owen Chapman and Kim Sawchuk (2015) categorized four different approaches to this process. [Note 5] For me, these approaches blend, merge, and mutate. Play, a vital part of artistic creativity (Huizinga, 1949, p.169), is the basis of my studio practice in subject matter (drawing and painting my children and their toys) and in techniques. In a previous series, I repurposed children’s toys into paintbrushes in my Motherhood Hit Me Like a Train series. [Note 6] Play is a way to multitask and meld mothering and art making by simultaneously doing both. I bring silliness and play to the artist’s statements I write to describe the visual work. [Note 7]

An artist needs space and time to play (Huizinga, 1949). While play as expression and experimentation is encouraged for male artists, it is dismissed when practiced by mother artists (Chernick, 1992, p.20). Play occupies my thoughts, activities, and art practice. Documenting the objects of play, such as toys and stuffed animals, in my drawings, paintings, and writing, I ponder how my children play. When I play with them, I observe their lack of inhibitions, carefree use of materials, and innocent questions, all of which I take with me and incorporate into my studio work.

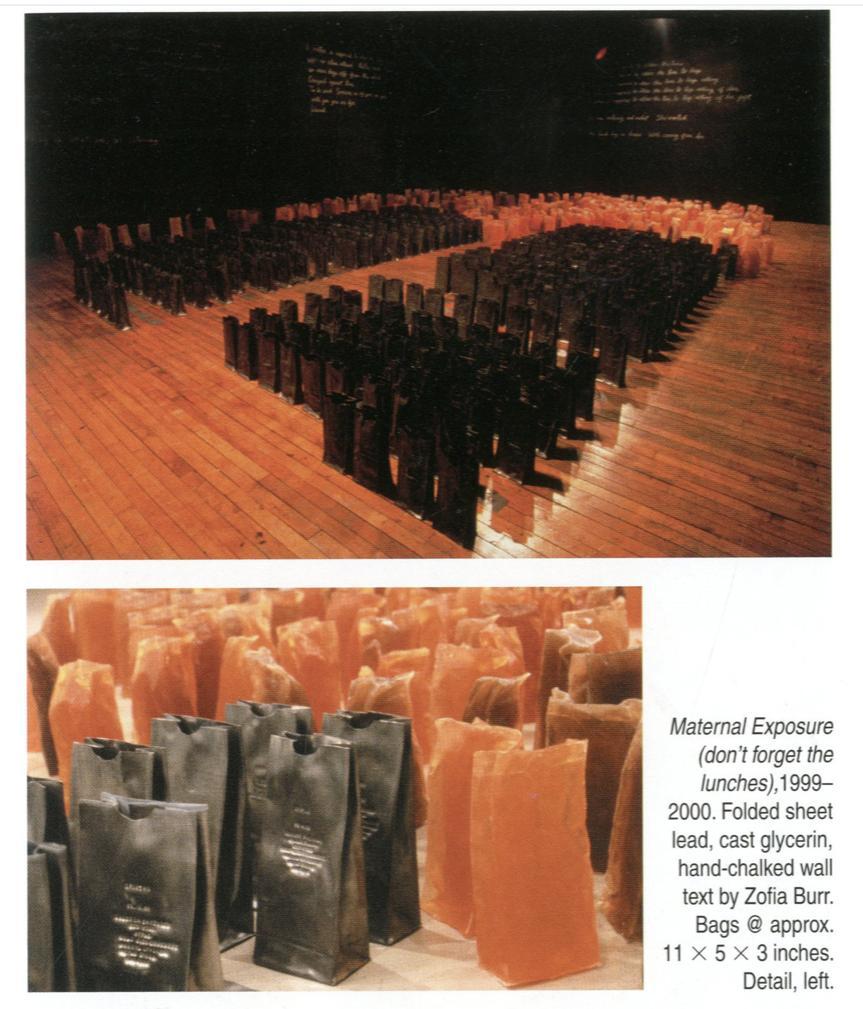

For other artist mothers, daily repetitive artmaking is a theme, as I have discovered in my research. Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973-79) and Monica Bock’s Maternal Exposure (or, don’t forget the lunches) (1999-2000) [Note 8] turn monotonous childcare routines and maternal ambivalence into monumental art series. In the quotidian scenes of messy maternal life, art routines are a reassuring way to create. My research addresses the question: How is the practice of an artist-mother visible, and how is it currently categorized in the visual arts? Concurrently, by what specific modalities do parents carve out space and time for work, art, family, and health, and what tactics might be employed? Motherwork is a care practice that involves not just the typical obligations of biological mothers, but all people doing mothering work as a central part of their life, as defined by Sarah Ruddick (2002). Immersed in Motherwork for over a decade, my art practice changed from long solitary studio sessions to artmaking bursts at home in between childcare tasks and among children. In conjunction with my art and studio research, my academic research centers on maternal bodies, including geriatric pregnancy experiences (a term used by my obstetrician/gynecologists each time I was pregnant) like mine, that “are ignored, stigmatized, or censored” (Epp and Reeves 2019, p.14). This work needs addressing and amplification because, according to art critic and writer Jori Finkel, “Motherwork is the last taboo in contemporary art” (Artbound, 2018). My work does not fit in Eti Wade’s (2016, p.275) established mother-art visual art categories [Note 9] or with seminal mother artworks such as Kelly’s Post-Partum Document. [Note 10] Because I incorporate play and humor in paint and mixed media from a mother’s perspective, my work evades current denominations. I need the space to test out large marks and transcribe monumental paintings into my own ideas.

Through writing and visual work, I concur with scholars that humor and play are urgent (Sillman, 2020, p. 41), and that women can both create and procreate (Chernick, 1992, p. 201). A favorite quote from Chernick laments that mother artists lack opportunity to play:

I wish it was not quite so difficult in this society for women to both create and procreate. I have observed that men (fathers or no) have greater freedom to “play” in their artwork, and to be taken seriously as artists for doing so. (p. 201)

Discussing this quote with another mother-artist scholar led us to wonder: what gives procreation the “pro” versus creation on its own? The “pro” in “procreate” is deceiving because mothers and parents procreate, but there is no training or professional accreditation for this achievement. Creation of any type seems like a difficult feat, particularly as we age.

Play serves to develop a mother’s creativity, for according to psychologist Susan Rubin Suleiman (1994), “[t]o imagine the mother playing is to recognize her most fully as a creative subject—autonomous and free, yet (or for that reason?) able to take the risk of ‘infinite expansion’ that goes with creativity” (p. 280). The studio is my place to play without interruption. Away from children, in my own space, spending time looking at my messy gestural sketches and complex compositional paintings leads me to create new work and to complete art in process. My studio’s three large white walls make me want to paint BIG. They inspire me to T a k e U p S p a c e. I dream of color, shapes, and painted creatures to fill the white walls with ample work and many small gestures.

I flip through my sketchbooks and art books when I need a new direction. My artwork done prior to 2023 was related to motherhood and to being stuck at home with young children. During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, the two series I created, “Motherhood Hit Me Like a Train” and “Mommy Mayhem,” [Note 11] were made during my pandemic parenting experience. The series are a response to my lockdown life and a way to work through my frustrations and to mock pandemic restrictions. More recently, I am ready to move on to a post-pandemic world where we can gather and have parties. I research paintings and artwork commissioned after past plagues, in line with scholar Natalie Loveless, who states that she “turn[s] to research-creation to encourage modes of temporal and material attunement within the academy that require slowing down in a way that does not fetishize the slow but in which slowness comes from the work of defamiliarization and the time it takes to ask questions differently. Research-creation has the capacity to impact our social and material conditions, not by offering more facts, differently figured, but by finding ways, through aesthetic encounters and events, to persuade us to care and to care differently.” (p. 107)

This year, I have been taking my time in transcribing artwork commissioned after past plagues as inspiration for new post-pandemic work. I loosely paint from large-scale Italian works commissioned after historic, memorable plagues, such as The Marriage Feast at Cana by Paolo Veronese [Note 12], and The Allegory of Good and Bad Government [Note 13], three fresco panels painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti between February 1338 and May 1339. These Italian paintings have many figures with complex compositions. My process of studying these works involves transcribing compositional and tonal elements of historical paintings into a new gestural, abstract work. When doing so, I always learn when drawing or painting from monumental paintings about formal art elements including using line, gesture, color, and shape. Writer Lydia Davis (2019b) advises going to “primary sources” and “the great works to learn technique” and reading “the best writers from all different periods; keep your reading of contemporaries in proportion—you do not want a steady diet of contemporary literature. You already belong to your time.” [Note 14] I look to the past for art ideas, image inspiration, and general learning. Davis also recommends reading solely from one’s own interest.

I loosely sketch from personal and historical sources, putting together compositions. Drawing informs my paintings and gives me more confidence with a paintbrush. I remember shadows and lines, building up muscle memory, meaning a neurological process that allows remembering certain motor skills and performing them without conscious effort. As I paint, I change some specifics of the original while creating my version. Instead of Renaissance-clad people, I alter the figures and add animals, my children’s toys, and imaginary creatures.

When I feel stuck about whether to fill the entire canvas/paper or leave blank canvas exposed, I draw from the paintings. I review my drawings and test ideas on paper, reverting to what is familiar and comforting: observational drawings from life and favourite historical artworks. These tactics provide a start or jumping-off point for my abstract, gestural paintings. The process is reassuring because I can learn from the strengths of good painting and drawing–excellent composition, tones, gestures, and marks. Transcribing allows me to strengthen my art and avoid feeling blocked, stalled, and repetitive. [15] Drawing from my own paintings allows me to pause and rethink the work. Like Matsutake mushrooms, which Anna Tsing explains do not easily change and refuse to scale up, I have “Some Problems with Scale[ing]” (Tsing, 2015, p. 43) my drawings to paint. My pencil sketches and written plans do not consistently translate well in oil or acrylic. Is this a boon or a bane? According to Tsing, the mushroom’s refusal to scale is considered a gift because the consistent refusal to stay small and intimate allows for transformative encounters that “create the possibilities of life” (p. 43). Similarly, sometimes my drawings need to stay small in black and white. They cannot and will not scale up to oil colour.

I revise and revise again, making lots of marks, erasure, wiping down paint and repainting the figures. Just as Davis revises one sentence, I can redraw one gesture, line or mark countless times. As discussed by Levine (2020), Rebecca Solnit and Michael Pollan praise slowness and do-it-yourself remedial practices to reclaim fractured time, with the “abstract” as Pollan’s enemy in Cooked (p. 209). The kitchen is Pollan’s “antidote to what he describes as the immateriality and anti-sensuality of computer work, including his own writing practice” (p. 209-10). Working in a tactile, patient manner with pencil drawing and oil painting is therapeutic and soothing compared to computer work. I must accept mistakes, slow down, and stay in the present. My time often feels like it is not my own, but at the mercy of family members, specifically my children. Studio time, however, is my time.

Despite my need for concentrated studio time, my best ideas and solutions to problems pop into my head when I am in the shower, going for a walk without listening to a podcast, or engaging in Jenny Odell’s version of doing nothing, which is, in fact, something: a form of rest, relaxation, cleansing of the digital world and a way of lettings ideas simmer. Odell explains,

I’m not actually encouraging anyone to “do nothing” in the larger sense… I believe that having recourse to periods of and spaces for “doing nothing” are even more important, because those are times and places that we think, reflect, heal, and sustain ourselves. It’s a kind of nothing that’s necessary for, at the end of the day, doing something. In this time of extreme overstimulation, I suggest that we reimagine #FOMO as #NOMO, the necessity of missing out, or if that bothers you, #NOSMO, the necessity of sometimes missing out. (p. 50)

I may miss out on gallery openings, lectures, and travel, but I am progressing in my work. Slowly but steadily, I make headway in accumulating marks, notes, and ideas. The gestures build up and form a knowledge mass from which I can pull when working in the studio. Learning from my children and the stolen minutes of artmaking between childcaring, I bring play, silliness, and experimentation into my studio practice. With my children’s daily influence, I cannot help but incorporate humour, whimsy, and color into my painting. It is often a time-saver and a respite from bright children’s colors to work in pencil and ink on paper. Black and white drawing into painting is my fallback method to create art. Thus, I conceive tactics to draw and paint amidst my children’s dribbles and crawls. Though these may have begun as scribbles and scrawls, their aggregation has led to my daily drawing series and body of artwork. The small moments in between mothering have accumulated into significant drawing knowledge, an important artmaking and research practice, and a large body of work.

Notes

[1] See an example of a collaborative drawing with my children in Appendix A.

[2] See Appendix B.

[3] See Appendix C for a photograph of my favourite drawing materials.

[4] I describe some of these projects on my Art Blog. See some examples: https://rachaelgrad.com/blogs/art-blog/tagged/drawings.

[5] “Research-for-creation,” 2. “Research-from-creation,” 3. “Creative presentations of research,” and 4. “Creation-as-research” (p. 49).

[6] See my fine art portfolio: https://www.rachaelgradart.com/colour-art-portfolio/motherhood-train-paintings

[7] See Appendix D

[8] See Appendix E

[9] Wade categorizes five distinct ways in which artist-mothers work with their “Maternal Material”: 1. Maternalist Materiality (employs maternal bodily excretion); 2. Maternal Refraction (employs mother’s gaze); 3. Intersubjective Maternalist Trace; 4. Politicized Maternal Multiplicity; and 5. Performance and the Raw (p.275). These categories include portrait photography, performance, and film.

[10] See Appendix E.

[11] See my art portfolio website: https://www.rachaelgradart.com/mommy-mayhem

[12] See Appendix F.

[13] See Appendix G.

[14] Davis’ recommendations for good writing habits also include: observe your own activity, feelings (but not at tiresome length), the behavior of others, both animal and human, the weather, and be specific; note technical/historical facts; always work (note, write) from your own interest, never from what you think you should be noting, or writing; be mostly self-taught; revise notes constantly—try to develop the ability to read them as though you had never seen them before, to see how well they communicate; take notes regularly and “grow” a story right then and there; and incorporate reported sentences or ideas from reality out of context. Davis notes that an advantage of “revising constantly, regardless of whether you’re ever going to “use” what you’ve written, is that you practice, constantly, reading with fresh eyes, reading as the person coming fresh to this, never having seen it before” (paragraph 31). See her web post: https://lithub.com/lydia-davis-ten-of-my-recommendations-for-good-writing-habits/

[15] See Appendix H for a photograph of my recent “After the Plague Party” paintings in the BIND art show, February 2023, at Special Projects Gallery, York University.

References

Alemani, C., (2022). The Milk of dreams. [Exhibition]. La Biennale di Venezia. https://www.ceciliaalemani.com/projects/the-milk-of-dreams

Bock, M. (1999-2000). Maternal exposure (don’t forget the lunches). In Chernick, M.& Klein, J. (Eds.), The M word: Real mothers in contemporary art (pp. 103-104). https://www.myrelchernick.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Maternal-Metaphors-Catalogue1.pdf. (2018). Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press.

Boon, M., & Levine, G., (Eds.) (2018) “Introduction.” In Practice (pp. 12-23) Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press.

Chapman, O. & Sawchuk, K. (2015). Creation-as-research:

Critical making in complex environments. RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 40(1), 49–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24327426

Carpenter Estrada, T., Moller Somsen, S. and Buteyn, K. (Eds) (2023). An Artist and a Mother. Demeter Press.

Chernick, M., & Klein, J. (2011). The M word: Real mothers in contemporary art. Demeter Press.

Chernick, M. (2001). From the M/E/A/N/I/N/G Forum: On motherhood, art, and apple pie. In M. Davey (Ed.), Mother reader: Essential writings on motherhood. Seven Stories Press (pp. 200-205).

Clayton, L. (2012). An Artist Residency in Motherhood. http://www.lenkaclayton.com/#/opensource-artistresidencyinmotherhood-1/

Davis, L. (2019a). Revising one sentence. Essays one (pp.141-168). Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Davis, L. (2019b). Ten of my recommendations for good writing habits. https://lithub.com/lydia-davis-ten-of-my-recommendations-for-good-writing-habits/

Epp, R. & Reed, C. (2019). Inappropriate bodies: Art, design, and maternity. Demeter Press.

Finkel, Jori. (2018, April 17). Artist and mother. (Season 9 Episode 7) [TV series episode]. In Artbound. Public Media Group of Southern California. https://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/episodes/artist-and-mother

Groys, B. (2002). The loneliness of the project. New York Magazine of Contemporary Art 1(1), https://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/472583/382bf1d01f310722b00babec2ee5b931.pdf

Heggeness, M. L., Fields, J., Trejo, Y. A. G., & Schulzetenberg, A. (2021). Tracking job losses for mothers of school-age children during a health crisis. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/moms-work-and-the-pandemic.html

Huber, M. & Kirtland, H. (2020). The motherhood of art. Schiffer Publishing.

Huizinga, J. (1949). Homo Ludens: A study of the play-element in culture. Routledge & K. Paul.

Kelly, M. Post-Partum Document, 1973–79. https://www.marykellyartist.com/post-partum-document-1973-79

Leclerc, K. (2020). Caring for their children: Impacts of COVID-19 on parents. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.g

Levine, G. (2020). Fermenting: Microcultural experiments and the politics of folk practice. In Art and Tradition in a Time of Uprisings (pp. 195–262). MIT.

Liss, A. (2009). Feminist art and the maternal. University of Minnesota Press.

Lorenzetti, A. (1338). The allegory of good government [painting]. Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy. https://www.comune.siena.it/node/174

Loveless, N. (Ed.). (2018). New maternalisms redux. University of Alberta Press.

Loveless, N. (2019). How to make art at the end of the world: A manifesto for research-creation. Duke University Press.

Loveless, N. S. (2015). Towards a manifesto on research-creation. RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 40(1), 52–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24327427

Malchiodi, C. (2007). The Art Therapy Sourcebook (2nd ed). McGraw Hill.

Marchevska, E. & Walkerdine, V. (2020). The maternal in creative work: Intergenerational discussions on motherhood and art. Routledge.

O’Reilly, A. (2021). Maternal theory: Essential readings. (2nd ed). Demeter Press.

O’Reilly, A. & Green, F. J. (2021). Mothers, mothering, and COVID-19: Dispatches from a pandemic. Demeter Press.

Ruddick, S. (2002). Maternal thinking: Toward a politics of peace. Beacon Press.

Schor, M. (2012). Wet on painting, feminism, and art culture. Duke University Press.

Sillman, A. (2020). Faux pas: Selected writings and drawings. After 8 Books.

Suleiman, S. R. (1994). Playing and motherhood. In D.

Bassin, M. Honey & M. M. Kaplan (Eds.). Representations of motherhood. (pp. 272-282).Yale University Press.

Swift, J. (2023). Art for self-care: Create powerful, healing art by listening to your inner voice. Quarry Books.

Truitt, A. (1984). Daybook, the journal of an artist. Penguin Books.

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

Turnbull, L. A. (2001). Double jeopardy: Motherwork and the law. Sumach Press.

Veronese, P. (1563). The marriage feast at Cana [painting]. Louvre Museum, Paris, France. https://www.louvre.fr/en

Wade, E. (2016). Maternal art practices: In support of new maternalist aesthetic forms. In R. Badruddoja & M. Motapanyane (Eds.), New maternalisms: Tales of motherwork (Dislodging the unthinkable) (pp 274-93). Demeter Press.

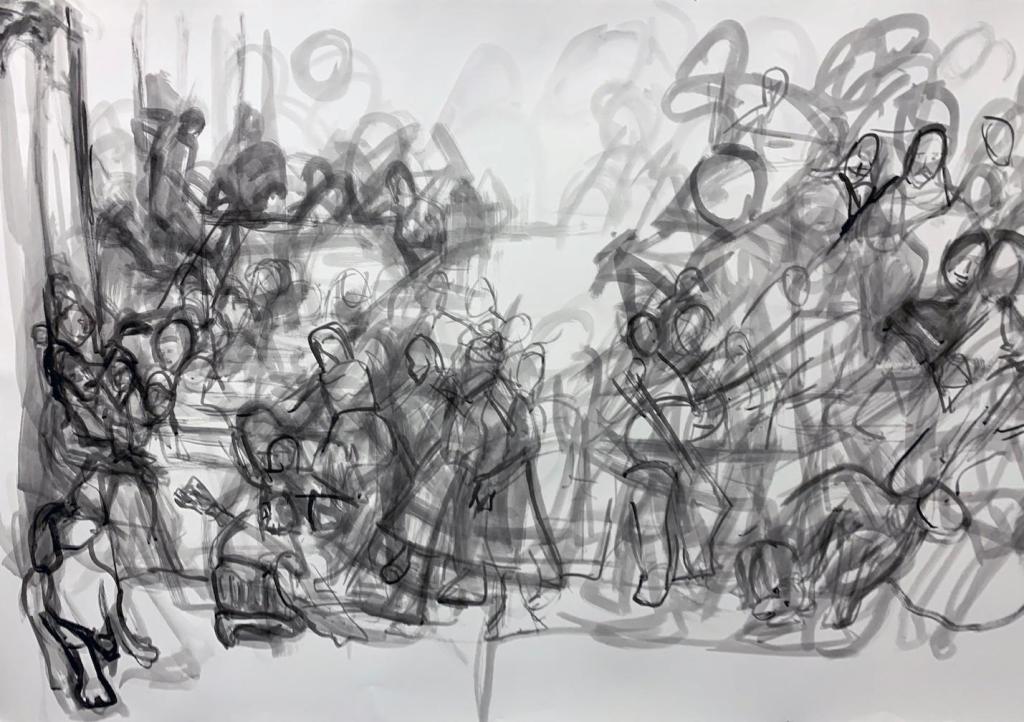

Appendix A

A sketchbook drawing from March 2023 with collaborative marks made by my children over my observational drawings of their toys.

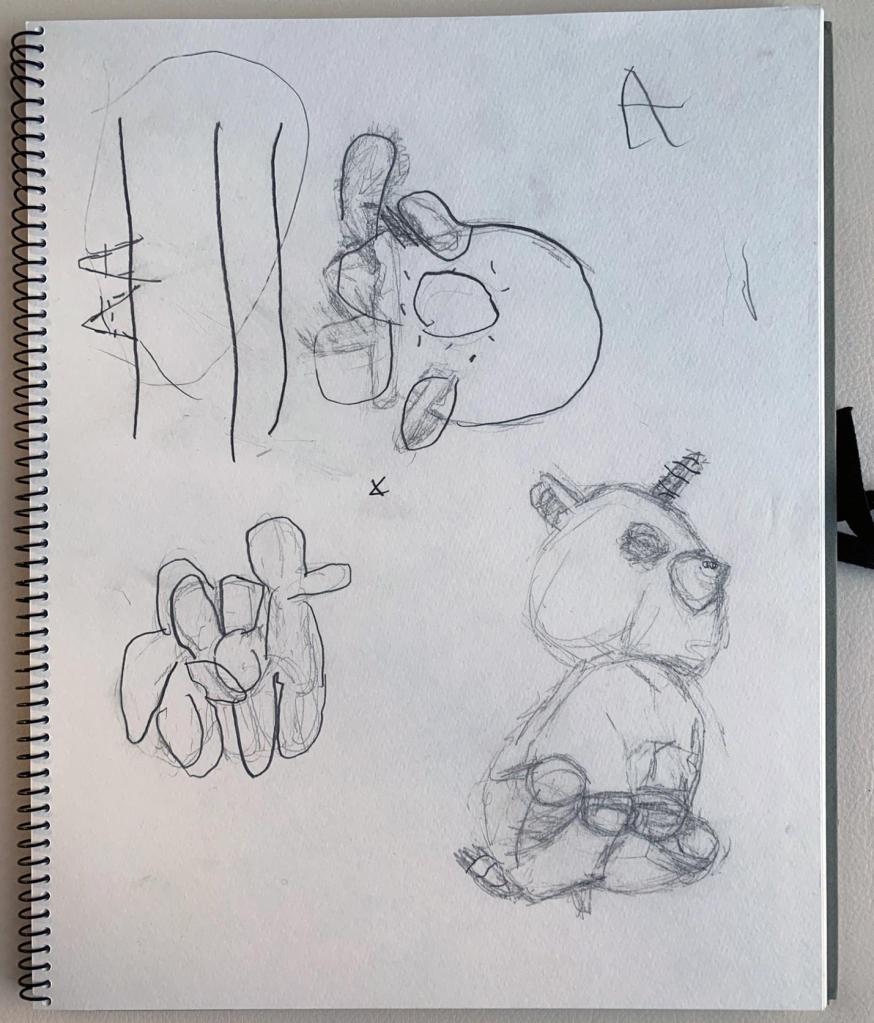

Appendix B

The cover of my “One Line a Day for 5 Years” Journal.

AppendixC

A photograph of my favourite sketchbook and drawing materials.

Appendix D

Example of my artist statement, 2022.

Appendix E

Monica Bock’s Maternal Exposure (or, don’t forget the lunches) (1999-2000).

Appendix F

The Marriage Feast at Cana by Paolo Veronese (1528-1588).

Appendix G

The Allegory of Good Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1290-1348).

Appendix H

A photograph of my recent paintings “After the Plague Party” (2023, Ink on Paper, 36” x 94”) and “After the Plague Party in Technicolour (2023, Oil on Canvas, 48” x 150″ in BIND Art Show, February 2023, Special Projects Gallery, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.