Angela Beallor and Elizabeth (EP) Press

As life collaborators— as lovers and co-parents, as organizers and agitators, in art and media-making– we have sought to cultivate spaces to explore questions and contradictions, creation and collaboration, often about the caretaking labor of our family life. The act of carving out space to collectively explore these elements, to grapple with the challenges through artistic collaboration, is not particularly groundbreaking. We desire creative space and a way to break the isolating tendencies of the familial household, where the work of home and childcare (on top of remunerative labor) takes temporal priority (Orozco, 2022, p. 99). [Note 1] This tension of time and energy is particularly challenging in a neoliberal society lacking in critical infrastructure to support most families and the extended networks of care labor (Hakim et al., 2020). We began this work together before the Covid-19 pandemic, an experience that heightened precarity and strained inequities in protection and care, illuminating the everyday challenges that already existed for many people and families.

Like so many who have come before us, our life-work and art-work explore how to be in the world and with each other and how to disrupt the more traditional models of isolated family life that we each experienced in our youth. We appreciate this forum, an exploration of reproductive landscapes, of un/doing motherhood, to intertwine and disrupt the dichotomies that pose “private” familial life and “public” artistic production and political engagement in opposition. Taking up discussions and discourses from those who have been asking what is meant by these terms motherhood/motherhood.As queer parents, we are trying to do something different, descended, as most queers are, from heteronormative families and frameworks. We are attempting to draft new lineages and ways to actively cultivate queer kinship. From the communities and networks of chosen families, cooperative homes, organizing collectives, artistic collaboratives, we bring what we have learned, the queerly cultivated ways of knowing, into our project of parenting.

Most of our artistic collaborations center around acts of caregiving, investigating this labor of the everyday, bringing out into the open what are often, in this contemporary moment, invisibilized activities (Orozco 2022, p. 113). [Note 2] We are guided by an expansive definition that finds care “at the heart of making and remaking the world”— and encompasses the myriad of “supporting activities that take place to make, remake, maintain, contain and repair the world we live in and the physical, emotional and intellectual capacities required to do so” (Dowling, 2021, p. 21).

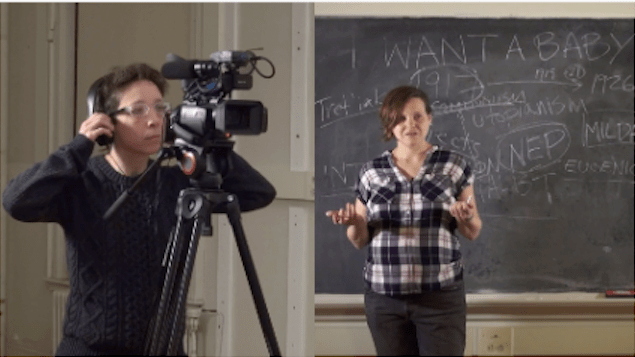

Figure 1. Angela Beallor and Elizabeth (EP) Press, I Want a Baby!, REVisited (Lecture), Single channel HD video, 24 mins, 2017.

When we decided to have a child, as queer partners, artistic collaboration was a way to explore the process of becoming parents. During pregnancy, we created the piece I Want a Baby!, REVisited (lecture) (2017), a lecture gloss about Sergei Tret’iakov’s censored Soviet 1926 play “Xochu Rebenka’”(I Want a Baby!). The play centers upon a cultural worker who is communally laboring with others to establish a collective nursery when she decides she wants to have a baby (without a romantic or parenting partner). Tret’iakov places the communal nursery, seen as a potentially liberatory childrearing option during the early stages of the Soviet experiment, at the center of the play’s plot. In an interview in 1927, Tret’iakov specifically stated that he wanted the play to bring “the measures of the Soviet government aimed at protecting motherhood and infancy [. . .] into the consciousness of women and mothers” (Tret’iakov, 1966, p. 198) [Note 3]

Through the medium of a scholarly lecture, we discuss the details and context of the play while traversing historical and contemporary themes of love, social change, utopia/dystopia, desire, pregnancy, eugenics, queer conception, artificial reproductive technologies, parthenogenesis, ‘lost causes,’ and more. Beallor delivers a lecture while Press is filmmaker, audience, and interlocutor. As Press interjects with questions and comments, a conversation about pregnancy, how we might parent, the relationship of community networks to family life, about queerness interrupts the lecture, bringing attention to the exchanges in our relationship and to the bodies at work (in numerous ways) in the space. Beallor is six months pregnant during the first lecture and our child appears in their arms as a four-month-old in the final lecture.

In the U.S. context, the landscape for queer parenting has changed dramatically during our lives— with the legalization of artificial reproductive technologies for LGBTQ+ people, an increase in the creation of LGBTQ+ informed care in medical settings, and parental rights for both biological and non-biological parents— largely set in motion by earlier gay and lesbian, queer and transgender liberation movements (Rivers, 2010, p. 918). [Note 4] Our choice to conceive and raise a child was pursued despite the persistent hostility still present in much of the world towards families like ours. Rapidly, with an anti-LGBTQ+ enmity in roaring resurgence, we encounter a clash of ideas, threats to our child, an idealism unattainable, in a world we continue to seek to collectively change.

The path to queer conception was not exactly clear, even with an extended network of queers who preceded us in having or attempting to have children. We conceived, birthed, and cared for our child through, against, and despite, what Sierra Holland (2019) describes as, “the tension between the ‘normal’ and the queer(ed)” (Holland, 2019, p. 53). We constructed queer parent-knowledge in the space between the medical institutions of the fertility clinic, the hospital, the pediatrician, and the “communal knowledge built by and for queer” people (p. 60). We, as so many before us have, straddled, and navigated the heteronormativity and homophobia of procreative institutions in order to birth otherwise, to queer, to attempt something else.

We are reminded of our queer familial ancestors in the Mother/Artist interview series, a part of the Performance and the Maternal research project. [Note 5] Performance artist Peggy Shaw (Split Britches) reflected on her experience as a parent in the 60s/70s:

“In the sixties and the seventies, in the lower east side [of New York] where my daughter Shara and I were, most lesbians weren’t raising kids. So it was hard. Most of her babysitters were actually drag queens rather than lesbians. She was raised by a lot of drag queens. . .. We got kicked out of hotels for being queer and having a kid. They thought we were sick or something. . .. It was really hard in those times. Some women in my neighborhood had sons and they actually gave them up because they felt like they wouldn’t be able to raise them very well in the queer community.” (Shaw, 2020)

Figure 2. Angela Beallor and Elizabeth (EP) Press, Pandemic Letter #1, Single-channel HD video, 2020

There is no certainty in bringing a child into the world: how it will go, who they will be, who we will be as parents, how the world will hold our child and how our child will hold the world. We knew we wanted to pursue different paths than our parents chose. This notion held some certainty, given the queer circumstances of our child’s path into this world. We were certain that we would try to raise our kid with expansive notions of identity and gender expression, casting a familial net of chosen family, things we didn’t necessarily have ourselves.

We care for our child, create a space for them to grow and to discover, we cultivate a space where we all continue to learn through our relationship and with each other. While we use the relational monikers “mama” and “mapa,” we have complicated entanglements with the idea of motherhood and the gendered associations with the term “mother.” [6] We wonder, as Alexis Pauline Gumbs writes, “[w]hat would it mean for us to take the word ‘mother’ less as a gendered identity and more as a possible action, a technology of transformation that those people who do the most mothering labor are teaching us right now” (Gumbs, 2016, p. 23)? Gumbs reflects on those rejected and refused from the status of Motherhood, a status granted “by patriarchy to white middle-class women, those women whose legal rights to their children are never questioned, regardless of who does the labor (the how) of keeping them alive” (Spillars, 1987, p. 23). [7] In our community, Angela is recognized more often, by others, as a mother. For example, she is the parent most invited to the mom gatherings. Maybe this is because she presents slightly more feminine or maybe this is because she has the shared birthing experience with many other moms. Or, maybe some combination of the two. It is not because of the division of mothering. This is shared – if not taken on more by EP. Regardless, caretaking [8] is enacted in our household. Historically idealized representations of Motherhood are disrupted by who we each are. Each of us have our own nuanced relationship to gender, as masculine, butch, androgynous, non-binary mothers/parents. Our ways of moving through the world elicit questions from our child (why is our family different?) and create space for critically engaging the ideas of binary gender that enter into the household through media, school, and conversations with friends. In the end, none of us neatly fit into the boxes created.

Co-parent Ari Dennis utilizes the term “ante-gender” to discuss their family’s decision to raise a child without an assigned gender (Winston, 2019). The prefix “ante” means “before” or “preceding”; this refers to the idea that an ante gender child is “before” gender, allowing the child time and space to figure out their relationship to gender themselves.While their family’s approach differs from ours, this idea of shaping a space for experimentation, play and discovery, before gender, feels close to the space we crafted in our home and relationships. This is a utopian idea in a world that is insistent on firmly knowing and yet, a way of being that we aspire to, and one that we have had some success cultivating. We do our best to cultivate a space of expansive gender play for our child.

With our now six-year-old, we are caring for a continually unfolding and becoming gender-creative child. The ways to support, advocate for, keep safe, and defend them in the current political climate is also not clear. Under the guise of defending children, the fascist and conservative right are waging legislative attacks and whipping up literal vigilante violent attacks upon transgender and LGBTQ+ people from state to state, [9] enacting anti-drag laws, banning gender affirmative care for transgender youth and adults, censoring informative and celebrative literature in schools, and forcing the cancellation of LGBTQ+ pride events and endeavors (Tannehill, 2023). [10]

The space of public school is generally a site of structured binary gender norms. At the start of kindergarten, our child wore dresses and sparkles and grew their hair long. They were referred to consistently as a girl for the first time and the majority of that school year became their first long-term experience in the gender binary. They were fine with it but this “close enough” experience in kindergarten led to the end of year scenario wherein our child broke the official story crafted by the teacher by deciding to use the other gendered (boy’s) bathroom. This caused a crisis for the teacher who panicked and acted as if our child had done something wrong. And, for us, we wanted to do better for our child moving forward. We described this “close enough” situation as falling on the more acceptable side of the binary for our child. Turns out, that was not good enough and we realized we need to be more proactive in advocating for a more expansive space of gender in their school as well. We connected with families at Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN), met with school administrators, counselors, social workers, and developed a “gender support plan” [11] with a useful resource from Gender Spectrum for the school setting. [13] We also connected with educators at our area Pride Center and reached out to LGBTQ+ members of the teacher’s union to see how we can advocate for more than just our child, particularly in this current political climate.

While LGBTQ+ people have the right to marry legally in the United States, being named on the birth certificate is not a legally binding document to acknowledge legal parentage of a non-biological parent. LGBTQ+ people are encouraged to pursue (and pay for) a second-parent adoption to affirm and protect parental rights.[3] In Florida, a measure was recently passed that can allow the state to rescind a parent’s custody if suspected of providing gender-affirmative care. Custody agreements from other states could be contested if a child is “likely to receive gender-affirming care in that second state” (Otten, 2023). It is all worrisome. How do we protect our own family and others? Or as Orozco (2022) asks, “How do we mobilize our mutual responsibility for sustaining life” (p. 272)?

MG (aka I Want a Baby! Reimagined)

In 2019, we returned to Tret’iakov’s 1927 play “I Want a Baby” (Xochu Rebenka). The central character of Tret’iakov’s script is Milda Grignau, a cultural worker constructing a collective nursery (one of the ways, at the time, to address gendered carework of the home and assist in broader participation in public life for women)— Milda decides that she would like to contribute a baby to the new Soviet society– without a lover, without a husband, without a parenting partner. With a Soviet eugenic eye, she tracks down Yakov, a 100% proletarian to help her with her task. The play centers her reproductive labor without actually depicting what this labor entails. This play, with all its quirks and complications, was perfect for an adaptation. This remake of the play, a queer, feminist, speculative re-imagining, explores adopting Milda Grignau— a rather serious cultural worker (who might today identify as butch) desiring a child and repulsed by the idea of a husband– as a queer ancestor. Valerie Rohy, in Lost Causes: Narrative, Etiology, and Queer Theory, interrogates the debates of queer reproduction and the reproduction of queerness often using literary examples. Rohy (2015) describes in Lost Causes: Narrative, Etiology, and Queer Theory, retroaction as reproduction.The drafting of affiliations across time, where “we might say that not only does homosexuality reproduce asexually, but it reproduces into the past, not by creating children but by creating the figurative ancestors who will then have preceded it” (p.141). This work was a layering of many reproductions.

Figure 3.Angela Beallor, M.G. (aka I Want a Baby!, Reimagined), multimedia performance, EMPAC, Troy, NY, 2019.

Tret’iakov’s Milda had a vision— to produce a proletariat baby to manifest the utopian visions of the burgeoning Soviet socialist state–a future-oriented anticipation of what this new being would become. We aren’t seeking to proffer this child, our child, or any child for any kind of specific future vision. As Jules Gill-Peterson (2018) writes in The Histories of the Transgender Child, “Children, by design deprived of civil rights and infantilized, are easy targets for political violence— just as easily, it turns out, as concerned adults can claim them for protection” (p. 2). In the name of the child, right-wing politicians and Christian conservatives are taking away our ability to care for and look out for our children, all our children, but in this instance most crucially queer and trans children.

Rohy (2015) notes how homophobic ideology is paranoid about queer proliferation— something that is being revived in current discourse— “through seduction, influence, recruitment, pedagogy, predation, and contagion” (p. 2). This is not literal gay parenting, she writes, but of course, that too is a contested site of potential homosexual influence and reproduction. We are interested in all these sites, both literal and figurative, for as Rohy writes, “imagining a world in which more homosexuals are welcome is essential to producing a world in which any homosexuals are welcome” (p. 186).

Other’s Milk and Milk of Many

At seven months old, our child was diagnosed as exhibiting “failure to thrive,” a downward change in growth attributed to difficulty breast-feeding, undiagnosed tongue and lip ties, resulting in a diminishing supply of milk. We faltered in feelings of failure as parents and found a way to respond with urgency. We found ourselves connecting with the unregulated shared milk community– resourcing donor human milk from friends, from local community members via our midwives, from people we didn’t know but found through Facebook groups made for this purpose. Karleen Gribble (2018) describes such peer-to-peer milk exchange as “a type of cooperative mothering . . . a social system wherein women (people) assist in the care of offspring who are not their own” (p. 8).

Some of our family members reacted with disgust when they realized our choice to continue to feed our kid with other people’s milk. We worried and questioned, as they did. We thought to ourselves were we possibly contaminating our kid? While others stayed in the realm of fear and revulsion over sharing another’s nourishment through bodily fluids, we mostly felt incredibly grateful and honored to be able to feed our child in this way. Press started to photograph the milk we were receiving via peer-to-peer milk sharing through a microscopic lens. We dove into research and art projects through this experience.

Figure 4.Elizabeth (EP) Press, Milk of many, digital photo of donor human milk through a microscope, 2020

Fiona Giles (E. Press, personal communication, May 13, 2019), the Australian scholar, writer, and feminist who has written extensively about human milk, shared in a 2019 video interview: “It is liquid gold. It’s special, it’s medicinal. And on the other hand, we think it’s disgusting and that it’s really difficult to hold those two in play.” We brought a queer sensibility to the peer-to-peer milk-sharing networks. As a form of mutual aid, donors share their milk for free. Often the only assurance about this bodily fluid exchange is one’s word that it is “safe.” This means that in a world where potential contaminants exist, transmitted via bodily fluids, those in peer networks are providing what can both nourish and possibly infect.

Giles further explained that it was in the 80s that milk banks in hospitals disappeared “because of HIV, AIDS and hepatitis C and other, fears around contamination.” While we were nervous about the exchange of bodily fluids without some sort of screening infrastructure like a milk bank, our trust was buoyed by the donor’s decision to freely share milk [14] with no monetary exchange when many options for commodifying this labor exist. In the end, our child was nourished by nearly two dozen donors.

When the issue of malnourishment arose, we had never heard of donor milk. The diagnosis from our pediatrician led us to consult with our midwives and we were soon connected to another family who had milk to donate (a surplus of pumped milk with which she was feeding her own child). We also learned from our midwife about informal donor milk networks. We connected to Eats on Feets and other communities via social media and email lists. We were trying to feed our child as much human milk as possible via these unregulated milk-sharing networks and thus developed a variety of donor relationships. Our friend, who gave birth a week before us, shared extra milk when she had it. We returned to certain local donors multiple times, meeting in parking lots and unloading their coolers of milk into our coolers. Sometimes, with the promise of a larger supply of frozen milk, we would drive further afield. Our risk assessment and decision making has been informed by a discourse once held mainly by queer community: those neglected by government support in the devastating experience of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 90s. The moral panic around queerness, coupled with the

structural negligence of care for those with HIV/AIDS, left queer people to develop strategies to care for each other when so much of society and government was violent and unwilling to provide support. Additionally, queer people sought to minimize risk that did not mean a strict abandonment of pleasure and physical intimacy. This weighing of risk in accepting breast milk from strangers felt akin to the stories of assessment we were familiar with from our queer elders.

Kane Race (2017) reflects on these strategies of harm reduction amongst queer people in the realm of HIV/AIDS where risk and safety are negotiated choices. Race describes modes of “embodied ethics,” when universally prescribed methods or a “normative morality” of avoidance stemming from fear of infection are less effective. Race writes, “Safe practice is an outcome of embodied habits, cultural memory, and sedimented history,” (p. 211) a kind of responsive “improvisation” that involves situational risk assessment rather than hardened boundaries. The choice to lean into what we don’t necessarily know–to trust the donors, the donated milk, to utilize the nourishment that is needed despite uncertainty–is a “negotiated safety.” There is much to unpack, and we are just attempting to hint at the various ways in which queer knowledge is reproduced, in the ways that the process has held us in our community and familial care work.

It feels important to note the difference between peer-to-peer milk-sharing networks and barter networks: those that give milk through informal sharing do not expect anything in exchange. Scholars like Narin Hassan (2010), Robyn Lee (2019), Carolyn Prouse (2021), and others have written extensively about the predatory practices of milk for profits. All milk exchanged in the communities of which we speak are never for financial gain; the buying and selling of human milk are clearly prohibited in these spaces. While these hyper-local peer exchange networks explicitly prohibit sales, the global exchange of human milk can and has been harnessed for profit. [15]

A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration “A Drawing Out :: Lactic Orchestration” (2018) is a performance work featuring the photograph that partially inspired the work: a group of laborers pumping breastmilk together, found in Fannina W. Halle’s 1932 book Die Frau in Sowjetrußland (published in English translation as Woman in Soviet Russia in 1934). [16] This photograph is slowly revealed in our animation,

Cell(ular) Formations, featuring microscopic video of donor breast milk and the photo in Halle’s book.

Figure 5.Angela Beallor and Elizabeth (EP) Press, Cell(ular) Formation, Digital Animation, 2018.

The performance itself comprises eight channels of audio, including six individually mic-ed electric pumps amplified during a live pumping session by three breastmilk-pumping performers. These sounds are mixed and performed for around 15-20 minutes, the length of a typical breast milk pumping session. The making of the piece required caretaking through and through as it was crafted and performed entirely by caretakers. It was care work beyond the nuclear family taken on by an artistic collaboration, creating community with each other while honoring the laborers of this kind of care.

As a way of ending, we want to circle back to the person who made us parents, to the collaborative work of care-taking our gender-creative child. It is with our kid that we are creating and learning, that we are crafting our history, our lineages, backwards, forwards, sideways.

As Rev. M. Jade Kaiser (2022) puts it in a liturgy from their project enfleshed, “This is indeed part of my queer agenda: To expose children as early as possible to all the possibilities of their beautiful becoming. To leave no doubt that whichever way their love blossoms and their gender blooms and their body unfurls, they will be protected, cherished, celebrated, loved.”

With our child, this is our care work – to make sure they know that they are loved despite the amplification otherwise from the conservative right. Our work in this is to make connections, across time, reproducing queerness and queer ways of knowing, along the way.

Notes:

1. In opposition to the tendency to think of familial households as isolated entities, Orozco writes, “Even if we live alone in a house, we do not organize our life in solitude but rather in networks.”

2. Care work is not merely invisible but rather structurally made not as visible while privileging certain labor, certain economics, certain people. Orozco writes, “The others, those who differ from that privileged subject, are inserted into the invisibilized spheres.”

3. Emma Dowling, The Care Crisis: What Caused It and How Can We End It?, Verso Books, 2021. https://www.versobooks.com/products/326-the-care-crisis.

4 While challenges to heterosexist notions of family and procreation were not overt demands in the earliest gay liberation movements, as more LGBTQ+ people felt emboldened to come out, exiting heterosexual relationships and marriages, battles over custody and familial rights surged in the 1970s. Rivers writes, “Lesbians and gay men had to fight hard to change the perception of parenting as exclusively heterosexual and the legal practices that supported it. Their uphill battle is an important part of both why and how domestic, parental, and marital rights came to be at the center of the modern lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) civil rights movement by the end of the twentieth century.

5 The Performance and the Maternal research project “seeks to better understand the condition of the maternal through a study of maternal performance. It is driven by researching both the conditions in which mother artists make work and the contexts in which that work is received.” A project led by scholars at the University of South Wales (Cardiff) and Edge Hill University (Ormskirk).

[6] The queer and feminist discourse around the term “mother” and the concept of “motherhood” has been rich and ongoing. Andrea O’Reilly’s scholarship has analyzed the various dictates and expectations stuffed into the patriarchal concept of “motherhood” and has, through a polyphony of voices and experiences, disrupted and challenged these concepts through examples of what she calls “empowered mothering.” O’Reilly posits mothering as a verb, explores the intricacies of gender-expansive mothering, and attempts to reconcile the need to acknowledge the deeply gendered nature of motherhood while also expanding mother-work in a queer and non-binary manner. Andrea O’Reilly, Matricentric Feminism: Theory, Activism, and Practice, Bradford, ON: Demeter Press, 2016. See also Andrea O’Reilly, ed., Mothers, Mothering and Motherhood across Cultural Differences: A Reader. Bradford, ON: Demeter Press, 2014.

[7] Gumbs is referencing Spillars’ foundational text challenging white supremacist and patriarchal notions of “motherHOOD.”

[8] Through the process of writing this together, we find ourselves slipping between caretaking, caregiving, and mothering. This reflects both a discomfort with the term mothering and also a gravitation towards it. Really, this acknowledges a lack of terms in common parlance that can hold queer, non-binary, and less gendered expressions and experiences.

[9] Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures in 2023 increase exponentially as similar bills are introduced in states across the country. In the last few years states have advanced a record number of bills that attack LGBTQ rights, especially transgender youth and this year according to Human Rights Watch there are more anti trans bills proposed than ever before. https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights.

[10] Attacking and criminalizing queer and transgender people is a priority clearly defined for the next conservative presidential hopeful. While we watch the testing ground unfold in DeSantis’ Florida, the plan is clearly spelled out by Project 2025 and their playbook “Mandate for Leadership: A Conservative Promise.”

[11] Gender Spectrum “Gender Support Plan”, https://www.genderspectrum.org/

[12] Since first writing this, we found this 2023 resource incredibly useful. The New York State Education Department’s Creating a Safe, Supportive, and Affirming School Environment for Transgender and Gender Expansive Students: 2023 Legal Update and Best Practices https://www.nysed.gov/sites/default/files/programs/student-support-services/creating-a-safe-supportive-and-affirming-school-environment-for-transgender-and-gender-expansive-students.pdf

[13] More information on secondary adoption can be found here: https://www.familyequality.org/resources/confirmatory-adoption/

[14] While in this article we are reflecting on the nourishing value of voluntarily shared human milk and the possibilities for this mutual aid to transform into a more politicized network, Prouse (2021) and others interrogate the economic valuation of human milk. The commodification and circulation of this biocapital is an equally significant site for critique and contestation. The various factors at play that may impact the decision to sell or share and the potential for exploitation of disenfranchised people in this monetized circulation are complex and an important part of this conversation.

[15] Curious how many of those peers participating in human milk exchange and mutual aid see the broader ethical and political implications of this work? Will these networks ever become a deliberate space to challenge heteronormative, nuclear family isolation? What is the potential of these alternative networks existing under the radar and outside of regulatory and/or capitalist modes of exchange?

[16] The reproduction in Halle’s book is an uncredited photograph of a photograph and was likely found in the 1931 book Der Staat ohne Arbeitslose: drei Jahre “Fünfjahresplan” (The State Without Unemployment: Three years of the Five-Year Plan), Ernst Glaeser and Franz Carl Weiskopf, a collection of photographs curated from the illustrated magazine Ogoniok (Moscow) and Unionbild (Berlin). Captions in both books do not provide a thorough description of the image: who took it, where it was taken, who is depicted in the photograph, etc. Glaeser/Weiskopf’s book does provide a series of photographs and leads the viewer to surmise that this milk is then combined to feed children in a nursery, creche, or children’s home. For more on the work of Weiskopf and this book see Müller (2019).

References:

Dowling, E. (2021). The care crisis. What caused it and how can we end it? Verso Books. Fevral’skii, A. (1966) S. M. Tret’iakov v teatre Meierkhol’da. In Tret’iakov, S.M., Slyshish’,Moskva?! (pp. 186-206) Issustvo.

Gill-Peterson, J. (2018) Histories of the transgender child. University of Minnesota Press.

Gribble, K. 2018. “Someone’s generosity has formed a bond between us”: Interpersonal

relationships in internet-facilitated peer-to-peer milk sharing. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14 (S6), e12575. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12575

Glaeser/Weiskopf’s book does provide a series of photographs and leads the viewer to surmise that this milk is then combined to feed children in a nursery, creche, or children’s home. For more on the work of Weiskopf and this book see Müller (2019).

Gumbs, A.P. (2016). M/other ourselves: A Black queer feminist genealogy for radical mothering. In A.P. Gumbs, C. Martens, and M. Williams (Eds.), Revolutionary mothering: Love on the frontlines (pp. 19-31). BTL Books.

Hakim, J., Chatzidakis, A., Littler, J., Rottenberg, C., and Segal, L. (2020). The care manifesto: The politics of interdependence. Verso Books.

Hassan, N. (2010) Milk markets: Technology, the lactating body, and new forms of consumption. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 38(3/4), 209–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20799376

Holland, S. (2019) Constructing queer mother-knowledge and negotiating medical authority in online lesbian pregnancy journals. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(1), 52-66. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12782

Lee, R. (2019) Commodifying compassion: Affective economies of human milk exchange. International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 12(2), 92-116. https://doi.org/10.3138/ijfab.12.2.06

Kaiser, M.J. (2022, March 11). On speaking queerly in public. enfleshed: spiritual nourishment for collective liberation, March 11, 2022. https://enfleshed.com/liturgy/lgbtqia-related/

Müller, M. (May 2019). Rifts in space-time: Franz Carl Weiskopf in the Soviet Union,” German Studies Review, 42(2), 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1353/gsr.2019.0047

O’Reilly, A. (2016). Matricentric feminism: Theory, activism, and practice. Demeter Press. O’Reilly, A. (Ed). (2014) Mothers, mothering and motherhood across cultural differences: A

reader. Demeter Press.

Orozco, A.P. (2022). The feminist subversion of the economy: Contributions for life against capital. L.M. Deese, Trans. Common Notions.

Otten, T. (2023, May 4). Florida passes bill allowing trans kids to be taken from their families. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/post/172444/florida-passes-bill-allowing-trans-kids-taken-families

Prouse, C. (2021). Mining liquid gold: The lively, contested terrain of human milk valuations. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53(5), 958–976. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X21993817

Race, K. (2017). Embodiments of safety. In Cipolla, C., Gupta, K., Rubin, D.A., and Willey, A. (Eds.), Queer feminist science studies: A reader (pp. 207-220). University of Washington Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcwn8vd

Rivers, D. (Summer 2010). “In the best interest of the child”: Lesbian and gay parenting custody cases, 1967-1985. Journal of Social History, 43(4), 917-943. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.0.0355

Rohy, V. (2015). Lost causes: narrative, etiology, and queer theory. Oxford University Press. Spillars, H. (1987) Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: A new American grammar book. Diacritics,17(2), 64-81. https://doi.org/10.2307/464747

Tannehill, B. (2023, August 14). The GOP has a master plan to criminalize being trans. Dame Magazine. https://www.damemagazine.com/2023/08/14/the-gop-has-a-master-plan-to-criminalize-being-tra ns/

Underwood-Lee, E. (2020, June 21). Interview with Peggy Shaw. https://performanceandthematernal.com/mother-artist-interviews/

Winston, Nama. (2019, May 19). ‘You got it wrong’: Sparrow and Hazel are being raised by multi-adult parents as ‘theybies,” Mamamia. https://www.mamamia.com.au/what-is-a-theyby/