By Kate Golding

*Content warning -In this paper I will discuss pregnancy loss. If this is a cause of concern for you, please do take care of yourself.

Recently my child and I were sitting together on the floor playing what is referred to as “talk them” in our house. This game involves holding the toys and talking for them. We needed to pause the game temporarily but my child refused, mainly because she knows that if she leaves a game I will invariably become distracted by some domestic task and the game will be over. Guessing that this was behind her refusal, I said, “I won’t go anywhere. I’ll remember what you were up to. I’ll be your memory keeper.”

Fig.1 Kate Golding, Kealakekua, Hawaiʻi, Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, 2012.

Fig. 2 Kate Golding, Lucy Wright Beach Park, Kauaʻi, Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, 2012.

The concept of “memory keeping” is something I’ve encountered a great deal in the decade I have spent researching and critiquing colonial monuments. However, it was the first time I’d used this term, “memory-keeper” in my caring role. Many theorists, writers and artists have spoken of the need to transform the memorial landscape particularly as the global pandemic and Black Lives Matter movement have made the inequities in the world even more visible.

Fig. 3 Kate Golding, Unlearning Cook, Part Three, 2016, 16 fixed lumen prints, 81cm x 102cm, unique work.

The debate around the problem of monuments is nuanced. Many call for the removal of monuments, some call for monuments to be altered or corrected, and of course there are those who wish to uphold the status quo. In October 2020 the worldwide shift to presenting events via Zoom meant I was able to attend an online in-conversation event about monuments between Zoé Samudzi and Nicholas Mirzoeff for The Lab. In this conversation Samudzi stated that whatever happens in the future of monuments and public remembrance we “can’t use identical forms” (Samudzi & Mirzoeff, 2020) to those of the past.

Monuments to care

At the start of 2020 I was able to move my child from 2 to 4 days of daycare per week. My intention was to move from freelance work to more stable employment. But by March of that year, I was in isolation with my then two- year old. As the year progressed, we were no longer able to access daycare since I was deemed a non-essential worker.

Over the next two years, embracing the paired isolations of extended lockdowns and primary caregiving, we undertook collaborative arts and craft projects. The works produced in this co-making practice operate as physical representations of memory, a record of caregiving and relational connection.

At first I saw no connection between this new work and my previous focus on monuments but I began to wonder if there is a way that the language of memorialization and monuments can be used to commemorate care? Or is that language so flawed that it makes it impossible to repurpose?

Upon searching the internet for “monuments to care,” the results presented are a list of websites addressing how to care for monuments. Not surprisingly, human milk and domestic caregiving are excluded from GDP while formula, cow’s milk and paid childcare are included (Smith, 2019 & 2022). In addition, women have overwhelmingly exited the workforce to provide caregiving during the pandemic (Wood, Griffiths & Crawley, 2021). In her book, Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change, Angela Garbes (2022) argues that mothering is essential work that is rendered invisible by the structures and systems in which many of us live, and that the pandemic showed just how essential that care-work is.

What can a monument be?

My research into monuments led me to question – what can a monument be? Can a plant be a monument? Can a journal be a monument? A poem or piece of writing? Can a body be a monument? Can care be monumental?

To return once again to Zoe Samudzi and Nichola Mirzoeff (2020), during their conversation there was a suggestion that a living monument that won’t be there for a lifetime avoids or undermines an imperial mindset. With this in mind, I began thinking through ephemeral monuments.

Near this spot was a temporary public art installation that I presented as part of PHOTO 2021 International Festival of Photography in Melbourne (See Fig. 4 & 5). During this project I explored this notion of a living monument by gifting packets of seeds to audience members. These were seeds of the indigenous plant, warrigal greens. Seeds were given to grow their own monuments. In an artist talk, I asked the recipients of the seeds the following:

“When you tend to them and give them care and they grow, you may think back to this moment – you may think of Captain Cook eating warrigal greens in 1770. Or that the Māori call them kohiki? Or that warrigal means wild dog in Dharug First Nations language? Perhaps you’ll think of regeneration. Perhaps you’ll be called to learn more about Aboriginal land management and farming. What is more potent? A living, ephemeral, embodied experience or walking past a statue of a dead white man and not caring who he is.”

My Granny, my dad’s mum, lived to be 99. She kept a book for what she called her “one liners.” Granny was not a comedian but instead these one liners consisted of one line of writing for each day. Since 2011 I have kept a similar daily journal. At the end of each day, I list everything of note that I did that day and some things for which I’m grateful. For the first year of my child’s life, the journal is virtually blank. Was the reason undiagnosed post natal depression, the monotony of each day, or not realizing how much was happening at the time? Now, all that time and memories have evaporated. Remembrance in this case was ephemeral. The journal could have served as a memorial to that time, filled with memories, perhaps in its lack of remembrance it still is.

Fig. 4 Kate Golding, Near this spot (2012-2020), PHOTO 2021 installation view, 12 photographs mounted on 6 double-sided aluminum panels, each panel 200 x 105cm. Photo by J Forsyth courtesy of Photo Australia.

Fig. 5 Kate Golding, Near this spot (2012-2020), PHOTO 2021 installation view, 12 photographs mounted on 6 double-sided aluminum panels, each panel 200 x 105cm. Photo by J Forsyth courtesy of Photo Australia.

In the second year of the pandemic, I lost a pregnancy. There were times during our six lockdowns here in Melbourne that we were only allowed out of our homes for one hour of exercise a day. I would often use that time to walk along a nearby creek and listen to a podcast. One day while out for a walk, not long after the miscarriage, I heard Irish poet Doireann Ní Ghríofa recite her poem, Sólas / Solace.

Sólás – Doireann Ní Ghríofa

(Nóta: Den Bhéaloideas é go bhfillfeadh anam an linbh mhairbh i

riocht an cheolaire chíbe is go dtabharfadh a ceol faoiseamh croí

don mháthair)

“Faoi cheo gealaí meán oíche,

de cheol caillte,

filleann sí ó chríocha ciana:

Aithním do bhall broinne,

a cheolaire chíbe

agus is fada liom go bhfillfidh tú arís

chugam.“

Solace

(Author’s note: In Irish folklore, souls of dead infants were believed

to return as sedge-warblers to comfort the mothers with song)

“Listen: in midnight

moon-mist, in snatches of lost music,

I’ve heard her return from the distance.

Little visitor, your birthmark looks so familiar.

Small warbler, listen, every night, I’ll wait,

awake, facing north, until the last star-light fades.

Find me, child; I yearn for your return.” (2018: p60-61)

I stopped walking and realized I was surrounded by birds singing in the eucalyptus trees. These were not warblers as in Ní Ghríofa’s poem, but nevertheless I was moved to tears thinking of the child who would never come to be. Ní Ghríofa’s website states that the poet’s writing examines “how the past makes itself known in the present” (2023, para. 1) much like the formal function of a monument.

Since that day, every time I have walked past that same spot, I have felt compelled to create some kind of temporary memorial in that place. Something ephemeral, a memory-keeper. “Near this spot a mother grieved the loss of her unborn child” made from bark or carved in the dirt, something impermanent. But then I question or worry that this compulsion to claim this particular space and place is my white, settler DNA and Eurocentric conditioning.

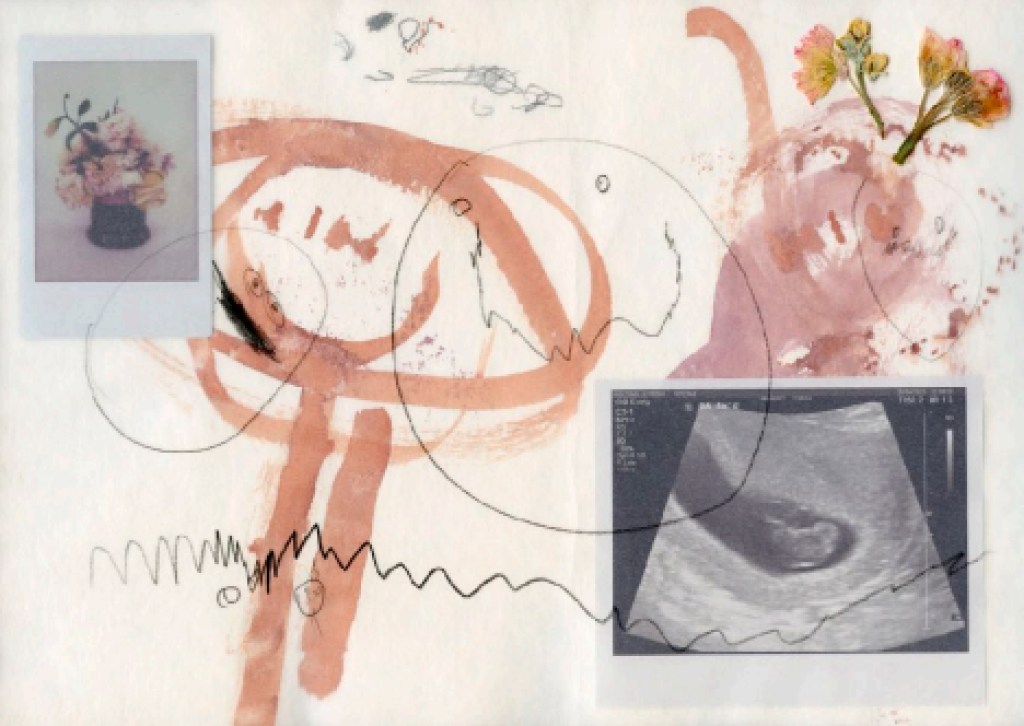

Fig. 6 Kate Golding and child, Untitled (8 weeks), 2021. Inkjet print, 100cm x 71.5cm.

Fig. 6 Untitled (8 weeks) is a collaborative collage that was created at home with my child in 2021. This work was made using a scanner and an assemblage of source materials available in our domestic environment, embracing our social isolation due to Covid lockdowns. Created in the aftermath of the pregnancy loss during the pandemic, it includes drawings and paintings my child, unaware of the miscarriage, made at the time. Other elements in the work include an Instax image of dead flowers sent to me by a close friend on the day of my D&C surgery, pressed flowers and the ultrasound image from the scan where I was told there was no longer a heartbeat. To me, this was the memorial I was searching for.

But where are the memorials to the tweens who have started to bleed, the eggs collected and frozen from aging ovaries, infertility, the endless rounds of IVF, the pregnancy loss, the D&Cs, the terminations, the queer parents, the birth givers who don’t identify as women, the birth givers who aren’t mothers, the trans men and non-binary pregnant people, those who have deliberately chosen to not have children, those who never got a chance to have children or to hold their children, the mother’s whose babies came to them via another’s body, the ambivalent parents, those in perimenopause, menopause, the hysterectomies, the endometriosis, the polycystic ovary syndrome, the reproductive landscapes too numerous to fathom?

Perhaps the memorials are written in our bodies. In our grief, in our joy, in our trauma and anger, in our numbing and longing. In every cesarean scar, in every episiotomy stitch, in every dilated cervix, in every irrevocably changed pelvic floor. In places seen and unseen, known and unknown. The body that has experienced pregnancy is changed, sometimes making that body unrecognizable to its lifelong inhabitant–changed by the temporary lodger/tenant/occupant/resident otherwise known as a baby.

In examining the idea of the body as monument further, I became aware of poet Caroline Randall Williams’ (2020) opinion piece in the New York Times titled “You Want a Confederate Monument? My Body is a Confederate Monument.” Williams speaks eloquently of her experience of being the descendant of enslaved African people and white rapists. Clearly the circumstances of Caroline Randall Williams’ understanding of her body as monument differ to those I am discussing here from my white settler colonial body. However, I believe our ideas are not entirely in opposition, as both seek to problematize current forms of monuments to contested histories while also envisaging future memory.

I acknowledge my experience of providing care is not unique nor is it universal. I am speaking of a very specific and personal experience of care. I speak from within this particular body. The 14 centimeter c-section scar that traverses my lower abdomen is a monument to an experience no less valid than that of a made- up or embellished colonial history someone chose to cast in bronze and erect on a stone plinth. An embodied monument will arise and fall through birth and then death. Our bodies, including those of our children, are living monuments that return to the earth from which they came.

Can care itself be a monument?

Caring for people, caring for planet and all its inhabitants, self-care.

To bring my learning throughout this period into the public sphere, I am currently facilitating a series of workshops and creating collaborative exhibitions. The aim of these projects is to build alliances between arts organizations, carers and those for whom they provide caregiving, while also welcoming families and children into art spaces – a place from which they are often excluded. These offerings will bring care-work and art-work into the public domain and offer an opportunity to build community.

Toddler art classes are being offered through a community arts center here in Melbourne. The program reaches diverse community members with the sessions designed for pre-school aged children and their carers. Participants collaborate on arts projects that are easy to replicate at home. The inspiration for the class design has been the co-making activities my child and I dreamed up during the pandemic and in her early years. I must also acknowledge the reciprocity of our caring relationship here – while I made snacks, provided shelter and entertainment, my child in turn cared for me through enabling me to express myself creatively too.

Fig. 7 Kate Golding and child, Mother’s Milk, 2018. Inkjet print, 29.7 x 42cm.

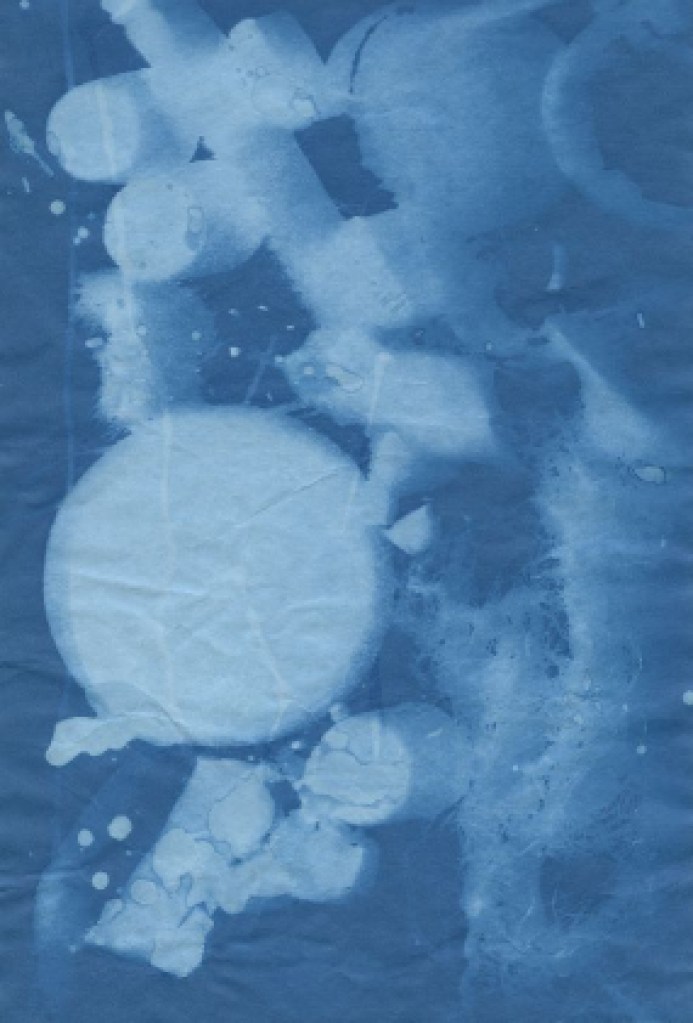

Fig. 8 Kate Golding and friends, Beach Plastic, K’gari, Butchulla Country, 2022. Cyanotype, 20 x 30 cm.

I exhibited a series of collaborative artworks at the Perth Centre for Photography in Australia in 2023. The exhibition, titled Labors of love, featured works created with several collaborators and was the result of our co-making art practice that occurs alongside care-work. For this mode of creation, the studio location had endless possibilities – the domestic space, outdoors in nature, or a social setting in which my community and I found ourselves. Having spent over a decade researching, critiquing and making art about the memorialization of colonial histories, my focus for this exhibition shifted to considering the insufficient number of memorializations acknowledging the significance of birth-giving, reproductive labor and care-work. The body of work of Labors of love acknowledges that much of the art-work and care-work carried out is undervalued and as a consequence goes unpaid or underpaid. Additionally, for future iterations of this work I have devised a series of public programs that will engage the local community including co-making activities for children and their carers, a reading group and child-friendly events in the gallery. This is a communal way of caring and remembering.

Reference List

Garbes, A. (2022). Essential labor: Mothering as social change, HarperWave.

Ní Ghríofa, D. (2018). Lies, Dedalus Press.

Ní Ghríofa, D. (2023). Doireann Ní Ghríofa. https://doireannnighriofa.com/

Randall, W, C. (2020). You want a Confederate monument? My body is a Confederate monument. The New York Times, 26 June, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/26/opinion/confederate monuments-racism.html

Samudzi, Z., & Mirzoeff, N. (2020). The Forum // Zoé Samudzi and Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Lab, [Video], October 22, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kJ1MPRjy4LU

Smith, J. (2019). The national breastfeeding strategy is a start, but if we really valued breast milk we’d put it in the GDP, The Conversation, August 5, 2019. https://theconversation.com/the-national breastfeeding-strategy-is-a-start-but-if-we-really-valued-breast-milk-wed-put-it-in-the gdp-121302

Smith, J. (2022). The mother’s milk tool: Putting a price on breastmilk, Broad Agenda, May 18, 2022. https:// http://www.broadagenda.com.au/2022/the-mothers-milk-tool-putting-a-price-breastmilk/ Wood, D., Griffiths, K., & Crawley, T. (2021). Women’s work: The impact of the COVID crisis on Australian women, Grattan Institute Report No. 2021-01, March 2021. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Womens work-Grattan-Institute-report.pdf