By: Amy Wagner, PT, DPT, PhD; Professor; Amy Crocker, PT, DPT, PhD; Susan Smith, PT, DPT, PhD

Abstract:

This paper focuses on the graphic representation of reproductive labor, from conception to birth, experienced by birthing persons as portrayed in comic art and graphic novels. Emotions around events associated with the reproductive process that seem taboo or “difficult,” such as infertility and miscarriage, can be expressed more effectively with the combination of text and images through the comic medium than in either alone. Non-normative reproductive journeys can be represented effectively through non-colonizing self-portrayals in comics, such as autobiographical graphic narratives of fertility treatments or pregnancy/birth with a disability. Theoretical frameworks to interpret graphic novels and comics material include matricentric feminism, motherhood studies, materiality theory, Foucault’s medical/clinical gaze, embodiment, maternal thinking, and decolonizing methodologies of constructing knowledge and being. Comic works discussed in this paper include graphic novels: My Body Created a Human: A Love Story, Kid Gloves, Graphic Reproduction, The Best We Could Do, and various webcomics.

Introduction

Birth is a life-changing event in the birthing person’s life course, in all circumstances. Pregnancy and childbirth have various meanings and outcomes for different individuals and may potentially be uneventful or traumatic; the process may follow a normative or non-normative path. When trauma arises at any point in the birth process or beyond, it has the potential to alter the individual’s life course through post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), fracture trust in the health care system, and create other life-changing effects for the individual and their loved ones.

Comics are a medium that may express the life events of pregnancy and childbirth in a meaningful way using text and images to convey emotion (McCloud & Martin, 1993). Emotions around events associated with the reproductive process that seem taboo or “difficult,” such as infertility and miscarriage, can be expressed authentically and effectively with the combination of both text and images in the comic medium (Chute, 2017). Comics center the patient’s voice (Venkatesan, 2021), and therefore can effectively represent self-portrayals of non-normative reproductive journeys such as pregnancy/birth with a disability or the use of fertility treatments among queer families. These non-normative experiences are important to represent, and provide a voice to those who may be less visible. In this way, comics can produce a decolonized (nonsubjugated) narrative to empower both the author and reader. The autobiographical format of the graphic memoir or comic allows the author’s voice to be heard directly, and not through a subjugated lens, increasing their voice.

The comic medium also has potential to increase empathy and affective response in the reader. The powerful combination of image and text in comics and graphic novels gives the opportunity for the reader to imagine the storyline arc in the “gutter” (space between panels), thus increasing the empathy of the audience engaged with this medium. Empathy is important for the audience to feel connected to the work, and enhance their own feeling of connection to the author’s experience. The purpose of this paper is to analyze graphic/comic works that represent motherhood across the reproductive continuum, from conception to birth, to interpret the lived reproductive experiences of women through this unique medium.

Theoretical Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are interpretive lenses that help interpret artistic works through a lens, to provide meaning and background. Rather than use one single or combined framework, multiple frameworks are used here to interpret the multiple and complex themes that arise in the graphic works. By combining frameworks, multiple perspectives can be explored. Theoretical frameworks to interpret the reproductive experiences in the lives of mothers as portrayed in graphic novels and comics,include: (1) those related to (normative) motherhood, matrescence, motherhood studies, maternal role attainment, matricentric feminism, and maternal thinking, (2) those related to comics, the body and vulnerability, as seen in the ideas of Ester Szép (Szép, 2020), and the broader concepts of embodiment and materiality theory (Baldanzi, 2022), and (3) frameworks related to power structures as highlighted in Foucault’s concept of the medical or clinical gaze (Foucault, 1963; Ristic, 2021) as well as decolonizing methodologies (Smith, 2019) of constructing knowledge. These frameworks provide a variety of theoretical lenses to view or explain the phenomena portrayed in each of the works. While distinct from one another, these frameworks collectively provide an overarching theme of reclaiming personal agency of the body during the reproductive cycle.

Theoretical Frameworks Related to Motherhood

Motherhood studies broadly explores the scholarly meaning of motherhood as an institution, experience and identity (Green, 2010). Frameworks related to motherhood on a personal level typically examine the change in identity from non-mother to mother. This is a major identity shift and is reflected in the concepts of matrescence and becoming a mother (BAM). Matresence is the rite of passage socially from wife to mother, and involves her group status, emotional life, daily activity, identity, and relationships (Raphael, 1975). Becoming a mother is described as the life-transformation involving growth and development of one’s persona which evolves over time (Mercer, 2004). Broader philosophical frameworks related to motherhood studies include matricentric feminism, motherhood studies, and normative motherhood. Andrea O’Reilly pioneered these fields. Normative motherhood is related to the concept of the “good mother” involving self-sacrifice (O’Reilly, 2023). Matricentric feminism is inclusive of mothers and is mother-centered. It sees mothering as a verb and does not limit mothers to biological mothers (O’Reilly, 2021). Maternal thinking (Ruddick, 1995) relates to maternal practice and the day-to-day activities performed by mothers. All of these frameworks point to the importance and value of motherhood, the daily activities involved, respect the transformational nature therein, and position the mother as central, not peripheral.

Theoretical Frameworks Related to the Body and Power Structures

Embodiment, materiality theory and the concept of comics and vulnerability are important frameworks for viewing these works (Baldanzi, 2022). Embodiment has been defined in a number of ways, including seeing the body as an active and engaged entity (Krieger, 2005). Szép (2020) describes the vulnerability of the body in the comic format. In the reproductive comics, the body is a prominent aspect of the work, and Szep also includes the body of the reader as an aspect of this vulnerability. The comic itself can be seen as a form of materiality (Godfrey-Meers, 2021) requiring physical engagement to read and interpret.

Power structures and imbalances are important frameworks to consider for women in reproductive stages, particularly since reproduction in the United States is generally viewed through the medical model. The medical model of childbirth is generally hierarchical; it views birth as a medical process and one to be managed. Importantly, Nietzsche created the concept of the medical or clinical gaze, in which the patient is viewed objectively through an observational lens (Foucault, 2002). The gaze of the healthcare provider becomes one of a power differential, although some believe that this power differential has decreased in recent years (Ristić, 2020). Some of the comic works in this paper can be interpreted through a lens of hierarchical power, where the mother’s voice is deemed inferior by the provider, even if inadvertently.

Another framework related to power structures is that of de-colonization. Decolonizing methodologies involves viewing an experience from one’s own perspective rather than the dominant culture, and is a resistance to colonialism (Smith, 2019). The comic graphic narrative can be seen as a form of autoethnography, a form of self-expression from one’s own perspective. Thus, the graphic novel or comic is a form of decolonized/reclaimed/resistance to the surveillance of the medical model of reproduction.

Works Discussed

Comic works discussed in this paper include graphic novels: My Body Created a Human: A Love Story, Kid Gloves, Graphic Reproduction, The Best We Could Do, and various webcomics. These works were selected to portray a wide representation of lived maternal experiences, both normative and non-normative. Graphic novels, books in comic format, are useful in showing long story narrative arcs with strong character development and rich content. Webcomics tend to be shorter and may only be one panel; they concisely portray experiences, political events, or personal narratives powerfully in an accessible way. Both formats are meaningful in portraying the hidden lived experiences in an autobiographical way, subverting power structures in the dominant culture.

My Body Created a Human: A Love Story

Emma Ahlquist’s My Body Created a Human: A Love Story, portrays the experience of first-time normative motherhood, including the processes of pregnancy and childbirth, including the bodily changes she underwent. Her story is one of multiple internal conflicts. She artistically shows, in graphic format, her inner conflicts between: (1) reproduction and climate change, (2) capitalistic pressure of doing and producing versus being a mother, (3) feminism/equality versus the author’s personal perception of full time motherhood not seen as complying with feminism in principle, and (4) community focus versus individualism. She describes her search for a new identity as both a mom and an artist.

Themes of this work include: matrescence/maternal role attainment as she becomes a first time mother and learns the daily roles involved, maternal thinking, and importantly in reference to her body, embodiment, and the physicality of motherhood including pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding. Ahlquists’ growing body is front and center in each panel showing how physical pregnancy is. She portrays mothering as a verb in her maternal thinking and practice in each chapter as she grows her body in pregnancy, completes daily tasks of motherhood, and breastfeeds. Through expressing her maternal journey in comic format, the reader can empathize and see themselves in her story, making it relatable and timeless.

Kid Gloves

In Kid Gloves: Nine Months of Careful Chaos, author Lucy Knisley experiences the life changing events of miscarriages, infertility, pregnancy and childbirth. She undergoes experiences that are a contrast between the ideals of a normative pregnancy and birth with her experience of medical emergencies and complications. Knisley brings to the page colorful comics portraying not only the factual history of women’s reproductive health care, interweaving these facts with her own traumatic experiences of miscarriage, infertility, and a delivery complicated by preeclampsia and eclampsia. Her work brings to light the invisible issues that women may emotionally experience but often do not discuss, using both humor and factual information to destigmatize them. Overcoming stigma of common maternal events helps to reduce shame and bring to light the real events of mother’s lives.

Graphic Reproduction: A Comics Anthology

Graphic Reproduction covers topics such as abortion, miscarriage, infertility, pregnancy, home birth, postpartum depression, and new motherhood. For example,”Overwhelmed, Anxious, and Angry: Navigating Postpartum Depression” normalizes the experience of postpartum depression, a taboo topic and health condition (see Figure 1). Through comic portrayal, stigmatized topics are made visible.

Visual storytelling in the piece allows for the expression of complex emotional and psychological states related to postpartum depression. This work allows for the portrayal of multiple perspectives: one panel depicts a clinical psychologist providing education to the reader using her eye gaze to appear to look directly at the reader, rather than other characters in the comic. Another panel depicts conversations between the psychologist and the parents’ sharing of their experiences, feelings, and fears, while the psychologist models how to provide support. This work represents a non-normative experience of motherhood. Motherhood is typically portrayed as a happy time period, yet this comic depicts mothers with postpartum depression who feel guilt, anger, and a sense of negativity about new motherhood. This honest depiction of postpartum depression resists the idealization of maternal happiness, bringing the legitimacy of frustration and anger during the postpartum experience to the foreground. The comic’s depiction of motherhood is an example of how visual representations of non dominant cultural narratives of motherhood can be destigmatizing.

The embodied narrative attends to the physical dimensions of the postpartum experience, including baby wearing and breastfeeding. The comic illustrates the body as a site of both trauma and recovery, highlighting the tension between the cultural abstraction of “mother” and the physical and material experience of motherhood. Using a mother-centered focus, the work illustrates the centrality of a woman’s mental health to her mothering experience. The comic’s theme is the necessary prioritization of new mothers’ mental health needs by allowing for communication of and destigmatization of maternal mental health struggles. Through integrated

Figure 1

Overwhelmed, Anxious, and Angry: Navigating Postpartum Depression

Note. This image is from “Overwhelmed, Anxious, and Angry: Navigating Postpartum Depression” (p. 182), by J. Zucker and R. Alexander-Tanner, from Graphic Reproduction: A Comics Anthology, 2018, The Pennsylvania University Press. Copyright 2018 by The Pennsylvania State University. Used with permission.

text and images, the work not only portrays the disorienting effects of postpartum depression but also models therapeutic care and healing. The comic educates, challenges cultural silences around maternal suffering, and normalizes and models a process of psychological self-awareness that may be inaccessible through text alone. By conveying empathy through the comic, the reader may see themselves or a loved one in the piece and seek care or increase their own self-empathy.

The Best We Could Do

The Best We Could Do is an intimate and poignant graphic novel portraying author Thi Bui’s family journey from war-torn Vietnam. Bui shares the struggle of adjusting to life as a first-time mother, persevering through what seems like an impossible journey to take on the role of both child and parent. She graphically examines both the strength of family and the importance of her own emerging identities as daughter, mother, wife, and her own self. The first chapter opens with the author depicted in the hospital, preparing to give birth to her first child. It is not only a personal account of the author’s experience of labor and childbirth, but also a reflection on motherhood and the intergenerational nature of trauma. Through the lens of childbirth, Bui begins her inquiry into the meaning of family, sacrifice, and the weight of her family’s history, including displacement after war. The experience of childbirth leads the author to reflect on her own mother’s experiences with suffering.

Several themes exist within this chapter. The theme of motherhood is introduced not only as a biological event, but as a psychological and emotional transformation. Bui’s experience of giving birth triggers a reevaluation of her relationship with her own mother, suggesting that empathy can be forged through their shared experiences. The images and text of her experience portray a view of pain and care that words might not alone.

Another theme is related to the cyclical nature of trauma, both personal, historical, and intergenerational. The author constructs a multilayered narrative that captures both the immediacy of her lived experience and the historical forces that shape it. The act of giving birth evokes the trauma of being born into a world shaped by war and displacement. The author does not feel ready to be a mother and questions her capability, has difficulty with breastfeeding while

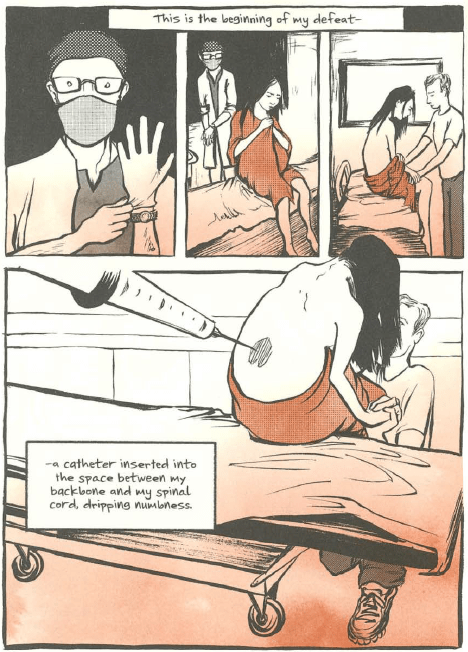

hearing another mother, her roommate, who is easily able to satisfy her child’s hunger, highlighting her struggle with maternal role attainment. Through the process of labor, the author feels a loss of autonomy, about her body and choices, to healthcare providers, and feels like an object rather than a person, highlighting the medical/clinical gaze power dynamic and colonization due to racial differences and decreased personal agency (see Figure 2).

The author depicts the trauma of feeling abandoned by her mother, who came to town to be a support during labor and childbirth but disappears multiple times after labor begins. The following morning, the author’s mother returns and shares her own experiences of being alone during the birth of her six children, and expresses that she is proud of the author. The chapter ends with the birth of her child and the symbolic birth of her understanding that if she is to comprehend her mother’s trauma, she must delve into the past. The use of graphics allows for a visual mapping of this embodied history, where pain is not only described, but seen, and the author uses this medium to address, confront, and process ineffable aspects of familial and cultural trauma. The author realizes that family is something she created, not merely something she was born into, that the responsibility of that is immense, and a wave of empathy for her mother washes over her (see Figure 3).

Figure 2

The Best We Could Do: The Epidural

Note. This image is from The Best We Could Do (p. 8), by T. Bui, 2017, Abrams, ComicArts. Used with permission.

Figure 3

The Best We Could Do: Family

Note. This image is from The Best We Could Do (p. 21), by T. Bui, 2017, Abrams ComicArts. Used with permission.

Webcomics

Webcomics (comics published digitally online) can provide powerful visual representations of emotions that may not be as easily understood in another format, such as through text alone. Digital publication may also increase access to a different or broader audience than traditional publication, especially if self-published or via social media. The combination of text and images can capture moments of mothering that are largely universal, yet are often undiscussed and therefore invisible. These invisible aspects of mothering are powerful and can bring up emotions and memories that may be difficult to put into words. Webcomics serve as a representation of time and memory, representing relatable events that may even mimic current events (Abrecht, 2012).

“We Might Never Know Why” is an excerpt from Paula Knight’s The Facts of Life, featured in Mutha Magazine that focuses on miscarriage, including the complicated emotions associated with a positive pregnancy test and insensitive comments post- miscarriage. The visual of waves is interspersed throughout the graphics to mimic the ebb and flow of emotions. Using comics to convey the message allows the reader to become immersed in the story in a way that a narrative does not. In one scene set in a waiting room, the visual depiction of diverted eyes and faces full of worry and strain, speaks volumes to the lived experience of miscarriage that is often not discussed. The ability to shine a light on invisible experiences is something seen frequently in comics in Mutha Magazine that explores all areas of pregnancy, birthing, and motherhood, using the framework of vulnerability, and embodiment, making the pregnant and non-pregnant body seen.

Another use of comics for the author is as a sort of therapy, particularly as a way to process trauma. Comic representation of birth trauma demonstrates the need for a trauma informed approach and shared decision making during the birth experience as well as how birth is often viewed through a medical gaze – where the mother and child are viewed more as objects in the birthing process versus being a partner in the decision-making team. Given that between 20 and 48% of women describe their birth experience as traumatic, with three to four percent of women experiencing PTSD after their birth experience, comics have an important educational implication for readers (Andersson et al, 2024).

In comics, the viewpoint is often first-person with the reader able to “hear” the inner thoughts and feelings of the characters. Comics can be used to shed light on current political issues like the image in Figure 4, by Henny Beaumont, which highlights the current midwife shortage in the UK. This comic depicts childbirth through a medical gaze, a process stripped down to merely a medical procedure and creating a power dynamic that is automated to increase efficiency. The pregnant body is under a medical gaze as well as surveillance, to monitor the birth process.

Figure 4

I’ve Thought of a Great Way to Tackle Midwife Shortages

Note. An image that shows the medicalization of midwifery in England. Reprinted from Henny Beaumont by H.Beaumont, 2017, https://hennybeaumont.com/#/politicalcartoons/. Reprinted with permission.

Discussion

Graphic memoirs function as a decolonized medium by virtue of their autobiographical nature, direct emotional expression, and engagement with taboo or silenced topics. The combination of images and text enhances empathy for lived experiences and facilitates co-constructed meaning between the author and reader. These visual narratives challenge dominant, medicalized, or normative representations of reproduction by centering voices often marginalized in mainstream discourse. Within the prevailing medical model of pregnancy, birthing persons are frequently viewed through a clinical lens that can diminish personal agency. Comics, by contrast, empower individuals to reclaim narrative authority over the physical, psychological, and social dimensions of motherhood.

Each reproductive journey is unique and may include non-normative experiences such as infertility, disability, queer family structures, or racialized encounters within healthcare systems.

Through embracing such diversity, comics serve as an inclusive vehicle for visibility and validation across intersections of race, class, gender identity, and ability. Also, comics hold significant value for health education and professional practice. Their accessible, first person storytelling is particularly effective for preparing healthcare providers to better understand the emotional and embodied realities of pregnancy, birth, and postpartum care (Moretti, Scavarda, & Green, 2025). Integrating these narratives into health professions education may promote trauma-informed, culturally competent, and person-centered approaches.

In addition, comics normalize and destigmatize mental health struggles in the perinatal period, such as postpartum depression, anxiety, and birth trauma. It should be noted that when comic books are offered to adult patients, providers should ensure the information is accurate and relevant as well as consider their patient’s openness to the format (Ashwal & Thomas, 2018). The visual format allows these challenges to be portrayed with nuance, modeling therapeutic interventions and offering readers a space for identification and empathy. This narrative accessibility supports both emotional healing and broader public awareness. Webcomics, in particular, expand the reach of these stories by circumventing traditional publishing barriers and inviting global engagement. Their immediacy and wide distribution allow for the exploration of contemporary issues such as reproductive rights, maternal health inequities, and systemic bias.

As tools for advocacy, comics have the capacity to illuminate systemic failures in healthcare, elevate marginalized voices, and inform public health discourse. Visual storytelling invites readers to witness and engage with lived experiences, promoting greater equity, inclusion, and accountability in reproductive care. Future scholarship might investigate how different audiences, such as clinicians, educators, policymakers, and patients, receive and respond to reproductive comics. Understanding their potential to impact empathy, communication, and health literacy can strengthen their application in both practice and policy. As this genre continues to grow, it remains critical to elevate diverse creators and reflect the full spectrum of reproductive lives in visual form.

Conclusion

Graphic novels and comics offer a powerful medium for representing the diverse, embodied, and often marginalized experiences of pregnancy, birth, and early motherhood. By combining autobiographical storytelling with visual narrative, comics challenge dominant culture and medical frameworks, elevate mental health awareness, and expand inclusive representations of reproductive life. Their accessibility, particularly through web based platforms, positions them as vital tools for health education, advocacy, and social change, with the potential to reshape public discourse and professional practice in reproductive care.

References

Abrecht, K. L. (2012). Illustrating identity: Feminist resistance in webcomics (Master’s thesis). San Diego State University. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.sdsu.edu/do/d8ad95ed-f623-4f7f-897f-7479733a1920

Andersson, H., Nieminen, K., Malmquist, A., & Grundström, H. (2024). Trauma-informed support after a complicated childbirth: An early intervention to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress, fear of childbirth, and mental illness. Sex & Reproductive Healthcare, 41, 101002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2024.101002

Ahlqvist, E. (2022). My body created a human: A love story. Chronicle Books.

Ashwal, G., & Thomas, A. (2018). Are comic books appropriate health education formats to offer adult patients? AMA Journal of Ethics, 20(2), 134–140.

Baldanzi, J. (2022). Bodies and boundaries in graphic fiction: Reading female and nonbinary characters. Routledge.

Bui, T. (2017). The best we could do: An illustrated memoir. Abrams.

Chute, H. (2017). Why comics? From underground to everywhere. HarperCollins.

Foucault, M. (2002). The birth of the clinic: An archaeology of medical perception. Routledge.

Godfrey-Meers A. (2021). A/effective bodies: A review of Eszter Szép’s Comics and the body: Drawing, reading, and vulnerability. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 11(1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.16995/cg.4769

Green, F.J. (2010). Motherhood studies. In A. O’Reilly (Ed.), Encyclopedia of motherhood (p. 832). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412979276.n441

Knisley, L. (2019). Kid gloves: Nine months of careful chaos. First Second.

Krieger, N. (2005). Embodiment: A conceptual glossary for epidemiology. Journal of

Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(5), 350–355.

Johnson, J. (Ed). (2018). Graphic reproduction: A comics anthology. Penn State Press.

McCloud, S., & Martin, M. (1993). Understanding comics: The invisible art (Vol. 106). Kitchen Sink Press.

Mercer, R. T. (2004). Becoming a mother versus maternal role attainment. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(3), 226–232.

Mitra, M., Long-Bellil, L. M., Iezzoni, L. I., Smeltzer, S. C., & Smith, L. D. (2016). Pregnancy among women with physical disabilities: Unmet needs and recommendations on navigating pregnancy. Disability and Health Journal, 9(3), 457–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.12.007

Moretti, V., Scavarda, A., & Green, M. J. (2025). Learning by drawing: Understanding the potential of comics-based courses in medical education through a qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 563. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-07120-y

O’Reilly, A. (2021). Matricentric feminism: Theory, activism, practice. Demeter Press.

O’Reilly, A. (Ed.). (2023). Normative motherhood: Regulations, representations, and reclamations. Demeter Press.

Raphael, D. (1975). Matrescence, becoming a mother, a “new/old” rite de passage. in Being female: Reproduction, power, and change (pp.65–71). De Gruyter Brill.

Ristic, A. J., Zaharijevic, A., Milicic, N. (2021). Foucault’s concept of clinical gaze today. Health Care Analysis, 29, 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-020-00402-0

Ruddick, S. (1995). Maternal thinking: Towards a politics of peace. Beacon.

Smith, L. T. (2019). Decolonizing research: Indigenous storywork as methodology. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Szép, E. (2020). Comics and the body: Drawing, reading, and vulnerability. The Ohio State University Press.

Venkatesan, V. & Murali, C. (2021). Drawing infertility: An interview with Paula Knight, Jenell Johnson, Emily Steinberg, and Phoebe Potts. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 12(5), 1187–1200. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2020.1764074